Georgians vote in high-stakes election over future in Europe

Pro-Western President Salome Zourabichvili said she was confident the vote would bring about the future all Georgians prayed for

Paul Kirby

Europe digital editor

Reporting from

Tbilisi, Georgia

Georgians are going to the polls to decide whether to end 12 years of increasingly authoritarian rule, in a decisive vote on their push to join the European Union.

Some see this election as the most crucial vote since Georgians backed independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. “I voted for a new Georgia,” said pro-Western President Salome Zourabichvili.

The governing Georgian Dream party is widely expected to come first, but four opposition groups believe they can combine forces to remove it from power and revive Georgia’s EU process.

Four out of every five voters are said to back joining the EU in this South Caucasus state, which fought a five-day war with Russia in 2008.

It was only last December that the EU made Georgia a candidate. But a few months ago it froze that bid, accusing the government of democratic backsliding, over a Russia-style law that requires groups to register as “pursuing the interests of a foreign power” if they receive 20% of funding from abroad.

About 3.5 million Georgians are eligible to vote until 16:00GMT in a high-stakes election that the opposition is calling a choice between Europe or Russia, but which the government frames as a matter of peace or war.

Politics here has become increasingly bitterly polarised, as Georgian Dream, under the guiding force of Georgia’s richest man, Bidzina Ivanishvili, seeks a fourth term of power.

Image source, Matthew Goddard/BBC

The Mother of Georgia sculpture welcomes visitors with a bowl of wine, but holds a sword to symbolise Georgia’s independence

If Ivanishvili’s party wins a big enough majority, he has vowed to ban the biggest opposition party, the United National Movement, because of its actions while in power before.

Georgian Dream, known as GD, is set to win about a third of the vote according to opinion polls, although they are widely seen as unreliable. If GD is to be unseated, all four of the main opposition groups will have to win upwards of 5% of the vote to qualify for the 150-seat parliament.

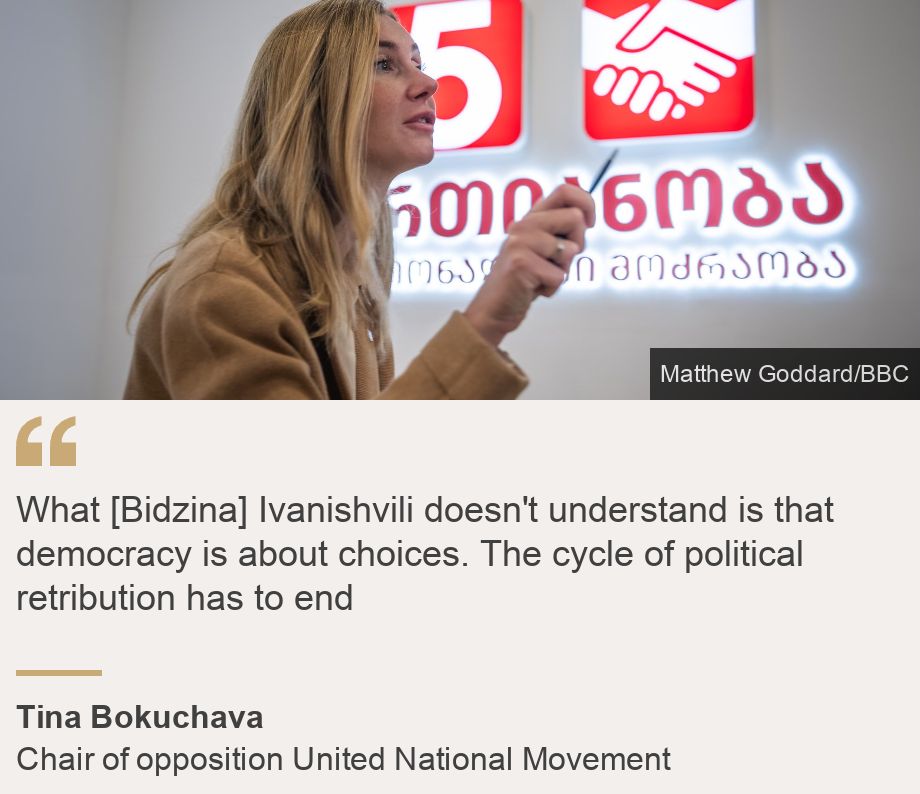

Matthew Goddard/BBC

What [Bidzina] Ivanishvili doesn’t understand is that democracy is about choices. The cycle of political retribution has to end

President Zourabichvili has been outspoken in her backing for a broad opposition coalition government, declaring that Saturday’s vote would bring an end to “one-party rule in Georgia”. As she voted shortly after polls opened on Saturday, she said there would be people “who are victorious, but no-one will lose”.

Zourabichvili has agreed a charter with the four big groups, external so that if they win, a technocrat government will fill the immediate vacuum. It would then reverse laws considered harmful to Georgia’s path to the EU and move to snap elections.

Tina Bokuchava, who’s chair of the biggest opposition party, United National Movement, insists all credible polls put the opposition ahead.

But Georgian Dream has told voters that an opposition victory will trigger war with Russia, and that message has proved effective beyond the big cities.

Party billboards across the country show split pictures of devastated cities in Ukraine alongside tranquil Georgia, with the slogan: “No to war! Choose peace.”

GD’s allegation against the opposition is that it will help the West open a new front in Russia’s war in Ukraine, while Georgian Dream will keep the peace with its Russian neighbour, which went to war with Georgia in 2008 and still occupies 20% of its territory.

Image source, Matthew Goddard/BBC

Georgian Dream’s national billboard campaign includes pictures showing devastation in Ukraine

Although the governing party’s claim is unfounded and its billboards have been widely condemned, its slogans appear to have resonated with at least some of the public.

In Kaspi, an industrial town to the north-west of Tbilisi, one woman aged 41 told the BBC: “I don’t like Georgian Dream, but I hate the [opposition United] National Movement – and at least we’ll be at peace.” Another woman called Lali, 68, said the opposition might bring Europe closer, but they would bring war too.

Hours before polls opened, the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy strongly criticised GD’s election campaign.

It highlighted instances of voters having ID cards seized as well as threats and intimidation, and pointed to Russian-sponsored disinformation operations as well as domestic campaigns.

The BBC spoke to one voter, Aleksandre, in a village north-west of the capital who said he had been threatened by a local GD man with losing his job if he did not sign up to vote for Georgian Dream: “I’m a bit scared of his threat but what can I do?”

However, Georgian Dream maintains it has made elections more transparent, with a new electronic system for vote counting.

“For 12 years we have an opposition that questions the legitimacy of Georgia’s government constantly. And that’s absolutely not a normal situation,” says Maka Bochorishvili, who’s GD’s head of the parliament’s EU integration committee.

Maka Bochorishvili says once Georgian Dream wins a fourth term it will sit down with the EU and find a way forward

“All this speculation about forcing people to vote for certain political parties – at the end of the day you’re alone and casting your vote, and electronic machines are counting that vote,” said Bochorishvili.

Critics say the changes have been brought in too hastily and that in some places there is a genuine fear that the vote is not really secret.

Not far from the centre of Tbilisi, Vano Chkhikvadze points to graffiti daubed in red on the walls and ground outside his office at the Civil Society Foundation.

After the “foreign influence” law was passed during the summer, in the face of mass protests in the centre of Tbilisi and other big cities, he says he was personally labelled by Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze as a state traitor.

“We were getting phone calls in the middle of the night. Our kids even were getting phone calls. They were threatened.”

Ahead of the vote, the EU warned that Georgian Dream’s actions “signal a shift towards authoritarianism”.

Whoever wins Saturday’s vote, the loser is unlikely to accept defeat easily.