Interpol has launched a campaign to identify a number of dead women

Reporting from

Wassenaar, The Netherlands & Le Cellier, France

A pair of red shoes, two beaded necklaces and a British 10p coin are among the few clues that could help to identify a teenage girl found murdered in western France more than 40 years ago.

Her death is one of 46 cold cases European police are seeking to solve as part of the second phase of a campaign aimed at finding the names of unidentified murdered women.

BBC coverage of last year’s appeal helped to identify a British woman some 30 years after her murder.

“We want to identify the deceased women, bring answers to families, and deliver justice to the victims,” Jürgen Stock, secretary-general of Interpol, which is co-ordinating the effort, said in a statement on Tuesday.

“Whether it is a memory, a tip, or a shared story, the smallest detail could help uncover the truth.”

The second phase of the Operation Identify Me campaign includes cases in the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, France, Italy and Spain.

Detective Franc Dannerolle is hoping to find the family of a teenage woman whose body was discovered in France

Details of each one have been published on Interpol’s website, along with photographs of possible identifying items and facial reconstructions.

Most of the victims are thought to have been aged between 15 and 30.

The body of the teenager with red shoes, beaded necklaces and a 10p piece was found underneath layers of leaves in a layby near a village called Le Cellier in 1982. It had been there for several months.

Speaking near the area she was found, now overgrown with brambles, nettles and horse chestnut trees, detective Franc Dannerolle says the teenager’s body was “disposed of like garbage”.

“There was no respect, no care for her before her death,” he adds.

The 10p coin led investigators to believe that she was either British or had been travelling in Britain before her murder, though they acknowledge that she could have found it, or been given it.

Police have chosen not to go into detail about the nature of her killing to avoid “fake perpetrators” from claiming responsibility.

Unfortunately, the teenager’s remains can no longer be found, which complicates the cold case investigators’ task.

“If we manage to find them, it could be possible to work on her DNA to have a link with the family,” says Det Dannerolle.

Alain Brillet has described the case as a ‘triple enigma’

Retired detective Alain Brillet worked on the case at the time and describes it as a “triple enigma”.

“The strangest and most incredible thing was that we had someone who had been murdered, because we knew she had been murdered, but we could never find out what her name was, where she was from, or who had killed her,” he says.

The BBC found one woman who recalled the fear the discovery of her body sparked in the village, but because the victim wasn’t local, most people forgot about it and moved on.

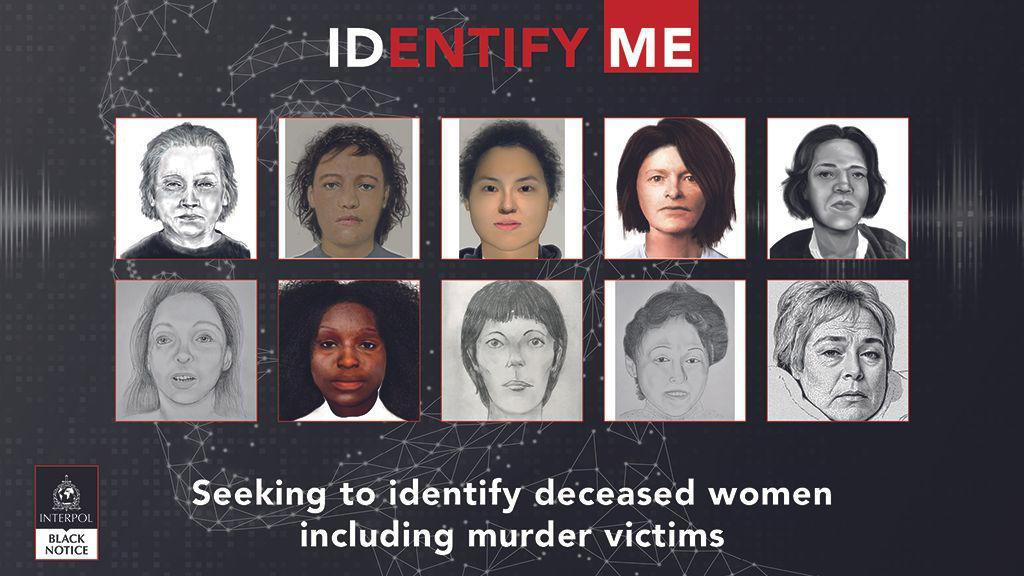

Image source, Interpol

Interpol has released sketches of women they are hoping to identify as part of the campaign

The launch of the Operation Identify Me campaign last year marked the first time that Interpol had ever gone public with a list known as “black notices”, seeking information about unidentified bodies. Such notices had historically only been circulated internally among Interpol’s network of police forces.

Across Europe, the ease of movement due to open borders, increased global migration, and human trafficking has led to more people being reported missing outside their home country, says Dr Susan Hitchin, co-ordinator of Interpol’s DNA unit.

“These women have suffered a double injustice. They’ve become victims twice: they’ve been killed through an act of violence and they’ve been denied their name in death,” she says.

Interpol is using targeted social media to advertise the campaign in specific locations and demographics. The global police force has also been asking celebrities to speak on behalf of the unknown, unnamed women.

Another case that Interpol is hoping people may be able to help solve is that of a woman whose body was discovered in Wassenaar in the Netherlands some two decades ago.

The discovery was Dutch forensic investigator Sandra Baasbank’s first case. She remembers seeing the woman lying face down in sand dunes, with no obvious signs of injury or struggle.

Sandra Baasbank is hopeful that the Identify Me campaign will help bring new leads

Det Baasbank says the woman was wearing brown plaid leggings and red shiny patent shoes – “unusual if you are going for a walk on the beach”.

“She was very fit, sporty. Wearing a headband, and sunglasses. Her buttons were done up and she was wearing a scarf,” the detective adds.

Forensic analysis found the woman was born in Eastern Europe and spent the final five years of her life in Western Europe.

One of the keys she was carrying was traced back to Germany.

“Maybe she made me better at what I do. ‘Never give up,’ is my motto. I’m determined in the work I do, and maybe she’s the reason why,” Det Baasbank says.

She is hopeful that the new Identify Me campaign will help ignite some new leads and provide a form of closure.

And there is reason for her optimism.

Image source, Interpol

Rita Roberts was successfully identified thanks to the campaign last year

Rita Roberts, a British woman murdered in Belgium, was identified when her family spotted her distinctive black rose tattoo in a BBC report based on the first appeal.

The last contact her family had with her was via a postcard in May 1992. Her body was found the following month.

When her family were told the body was indeed Rita, her sister Donna says she “broke into tears crying”. For them, it had ended decades of uncertainty.

While it has been hard learning of her sister’s death, she says she takes comfort in feeling that Rita is “at peace”.

Now she has been identified, her family are appealing to the public for any information however small to help with the investigation.

And they’re also hoping that other murdered women will also be identified.

They are “sisters, mothers, aunties,” Donna says. “Just because they don’t have names, don’t assume they’re not people.”

Additional reporting by Léontine Gallois