President John Dramani Mahama has issued a clarion call for what he terms Africa’s “Second Liberation”, one that moves beyond the political independence of the 20th century and aims to address the unfinished struggle for economic justice, dignity, and reparative equity for African peoples.

In a reflective opinion piece, he juxtaposes historical moments of Black resistance with the persistent legacy of economic apartheid.

President Mahama is calling out not only the distortions of history by global powers but also the urgent need for Africans to reclaim their narratives and resources in a new phase of self-determination.

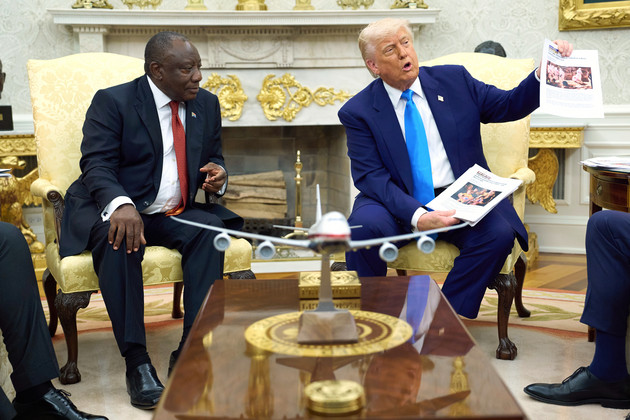

At the heart of Mahama’s essay is a critique of historical revisionism, most recently exemplified by U.S. President Donald Trump’s unfounded claims of “white genocide” in South Africa.

The President views such rhetoric not as mere misinformation, but as a continuation of colonial violence through language, a tactic long used to discredit Black agency and justify the erasure of systemic injustice.

Citing Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, he underscores that language conquest is cheaper and more effective than military domination, warning that silence in the face of such distortions only serves to extend the harm of past oppressions.

President Mahama’s central thesis is that while Africa’s first liberation brought political independence, the economic structures of colonialism remain largely intact.

He revisits Dr. Kwame Nkrumah’s declaration that Ghana’s independence was “meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa,” extending this logic to the present: Africa’s sovereignty remains compromised until economic justice is achieved.

Read also: John Mahama: Trump’s unfounded attack on Cyril Ramaphosa was an insult to all Africans

Citing persistent racial and economic disparities in post-apartheid South Africa, where white South Africans, who constitute less than 10% of the population, still control over 70% of the wealth, President Mahama argues that without reparative frameworks, the deep scars of oppression cannot heal.

He notes the continued existence of separatist, whites-only enclaves like Orania and Kleinfontein, as symbols of economic exclusion and social segregation.

Recounting his personal memory of the 1976 Soweto Uprising and the iconic image of Hector Pieterson’s lifeless body, Mahama emphasises the intergenerational trauma and solidarity that binds African peoples.

He recalls how Ghana, under Nkrumah, supported anti-apartheid struggles thousands of miles away because “people who looked like us were being subjugated”.

This pan-African spirit, Mahama argues, is not just a matter of history — it is a blueprint for Africa’s future.

Economic justice cannot be achieved in isolation; African nations must once again unite — this time to dismantle the structural imbalances of trade, wealth distribution, and global power dynamics.

Mahama links historical struggles with contemporary crises, from children dying in the mines of Congo, to rape as a weapon of war in Sudan, and the callous rejection of refugees by wealthy nations.

These, he insists, are the new battlegrounds of Africa’s Second Liberation — crises that reflect the enduring dehumanisation of African lives in a global system still shaped by imperial logics.

Quoting Desmond Tutu, “If you want to destroy a people, you destroy their memory”, Mahama defends the power of historical truth as a form of resistance.

For him, the stories of Africa’s pain and resilience must continue to be told, in classrooms, churches, salons, literature, music, and film.

This collective memory, he insists, keeps the spirit of liberation alive and guards against the erasure of hard-won progress.

For Mahama, the time has come to confront the unfinished business of Africa’s liberation. It is not enough to have political autonomy without economic power, or democratic systems without equitable resource control.

“We journey forward with a history that cannot be erased, and will not be erased,” he writes.

“Not while there are children dying in the mines of the Congo, and rape is being used as a weapon of war in Sudan.”

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.