A seat at the table or on the menu? Africa grapples with the new world order

Reuters

Reuters

Africa’s heads of state are gathering in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, for their annual meeting this weekend at a time when the continent’s place in the world appears to be in flux.

Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney, speaking in Davos last month, described an arresting image of the future of international relations: either countries were at the table or they were on the menu.

For Africa’s leaders, who for years have been arguing that they should be dining at the top table, it was not an unfamiliar analogy.

But in his second term, US President Donald Trump has accelerated the trend towards great-power domination of world affairs and the ditching of multilateralism.

As the White House’s updated security strategy says, not every region in the world can get equal attention. Trump’s pivot towards the Western hemisphere, as well as time spent on the Middle East, has implied less focus on Africa.

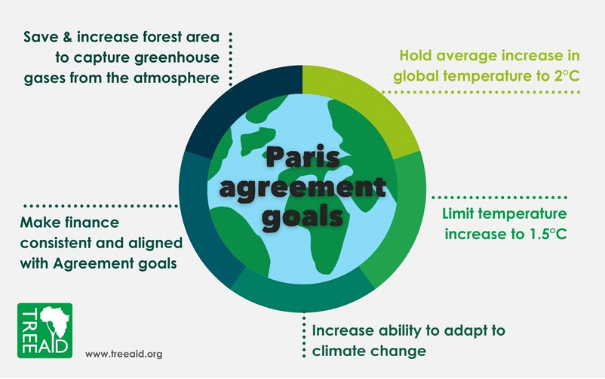

The less powerful nations, who may have once relied on the norms, as well as the finance, of global bodies such as the UN, World Bank or World Trade Organization, are now having to re-evaluate relationships.

These moves have given fresh urgency to the question of how the continent should deal with the rest of the world.

For Tighisti Amare, director of the Africa programme at the UK-based Chatham House think-tank, there is a danger that African countries will be “left behind” if they fail to develop an effective common strategy.

But already, for the US, there is a menu full of tempting bilateral deals involving minerals and natural resources, which bypass any opportunity for collective bargaining on the part of the continent.

When it comes to Africa, the policy shift reflected in pronouncements from Washington is dizzying.

EPA

EPA

A little over three years ago, then-President Joe Biden told the continent’s leaders at a summit in the US capital, that “the United States is all-in on Africa’s future”.

This followed a White House strategy document on sub-Saharan Africa which described the region as “critical to advancing our global priorities”.

Critics, however, have questioned whether this really did penetrate the Oval Office, with Biden’s only visit to sub-Saharan Africa as president – to Cape Verde, briefly, and Angola – coming in the last full month of his term.

In contrast to the official statements from his predecessor, Trump’s America First approach has a much narrower idea of US interests.

“We cannot afford to be equally attentive to every region and every problem in the world,” the White House’s National Security Strategy stated last November.

The three paragraphs on Africa at the end spoke about partnering with “select countries to ameliorate conflict, foster mutually beneficial trade relationships” and move from supplying aid to encouraging investment and economic growth.

For Peter Pham, who was a special envoy to Africa during Trump’s first administration, this is a more honest approach.

“I was trained in the realist school of international relations,” he told the BBC, “and I’m not delusional enough to think that Africa is front and centre of US interests as much as it’s maybe front and centre of my life.

“There’s no way any country, even a superpower, can be all things to everyone. The reality is we don’t have the bandwidth nor the resources, as generous as the American people have been, to do everything for everyone.

“So we have to husband those resources and steward them as best we can to achieve the optimal outcome for obviously our own citizens, but also our partners writ large.”

Getty Images

Getty Images

One of the clearest expressions of this was the minerals deal that the US struck with the Democratic Republic of Congo in December, which happened in tandem with the signing of a peace deal with Rwanda.

It was aimed at “building secure, reliable and durable supply chains for critical minerals” for the US, according to the text, as well as encouraging investment in DR Congo, which has huge reserves of minerals essential for the manufacture of electronic goods.

Pham himself is part of another deal as he is chairman of Ivanhoe Atlantic a company involved in the development of the “Liberty Corridor”, a project building new infrastructure linking Guinea’s vast iron ore mines to a Liberian port to boost exports of the raw material.

Ken Opalo, an Africa specialist at Georgetown University’s school of foreign service in Washington, is worried that the US’s transactional, bilateral approach “means that the bargaining position for African countries will be terribly weak and therefore they may not get the best deals possible”.

He told the BBC that if “the DR Congo example is anything to go by, the US focus on minerals is about merely securing mining rights for American companies and little else in terms of the broader economic co-operation, which is not what the region needs.

“The region needs deeper market access, investment treaties and the ability to attract US capital for all sectors not just mining.”

DR Congo’s Mines Minister Louis Watum Kabamba dismissed these concerns. Speaking at a mining summit in Cape Town this week, he said his country was not going to “sell everything for nothing to America”.

Other countries, such as Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates are also striking their own investment and security deals.

The transactional approach is not necessarily bad, Opalo said, but he argued that there is not the strategic depth of thinking going on, or diplomatic expertise, in African governments “to play this game well”. This means leaders may go for easy wins without considering the long-term implications, he feared.

On the security front, Africa’s failure to resolve the civil war in Sudan, triggering what the UN has called the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, could be seen as an example of this, Opalo added.

Despite its officially neutral stance, Turkey has been accused of supplying the Sudanese army with weapons. Iran and Russia also face the same accusation. All have been met with denials, but last February Russia signed a deal with Sudan’s military government to set up a naval base in the country.

On the other side, the UAE has been accused of backing the Rapid Support Forces, which it also denies.

“The failure to sort Sudan out is symptomatic of the lack of agency that the continent has,” Opalo said.

Reuters

Reuters

Ghana’s President John Mahama, for one, is trying to shift this assessment.

Mahama, like Carney, also spoke at the Swiss ski resort Davos.

He said that with “an unpredictable ally across the Atlantic” and shrinking development assistance, the world was at an “inflexion point”.

“Africa must pull itself up by its own bootstraps,” he argued.

In a passionate address he declared that the continent had lost its sovereignty and was caught in a dependency trap. This was true both in areas of aid spending – such as health and education – as well as security matters, he said, adding that when it comes to natural resources, “we supply the world’s critical minerals but capture almost none of the value”.

The president’s prescription, through his Accra Reset project, is more investment in relevant skills, co-ordinated industrialisation across Africa’s regions and joined-up continental negotiation with outside partners.

But these are calls that have been heard before and the question is whether there is a greater chance now that something will change.

For analyst Tighisti the “key challenge is that to create a united front, leaders should be more focused on regional interests. Sometimes this means that national interests have to be put aside if they really want agency in international negotiations.”

In his Davos speech, the Canadian prime minister called for the world’s “middle powers” to act together. In Africa these could include Nigeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya and South Africa.

But Tighisti said that while “these are the countries that everyone is looking up to, there is a lack of continental leadership to really push the integration agenda”.

One key problem is that many leaders are very inward-facing, as “they themselves have huge domestic challenges that they need to address at the same time”.

She added that there was already the framework for countries to work more closely through things such as the continent’s free trade area – a project aimed at boosting commerce between African countries – and the African Union’s Agenda 2063, described as a master plan for transforming the continent, but progress on these has been slow.

Laying out his pitch in Switzerland, Mahama said that “Africa intends to be at the table in determining what that new global order will look like”.

But there is still a lot of work to do to get the most out of the shift in US foreign policy as well as the continent’s other partners – the dinner invitations are not yet being sent out.

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC