Soutik BiswasIndia correspondent, Dhaka

Reuters

Reuters

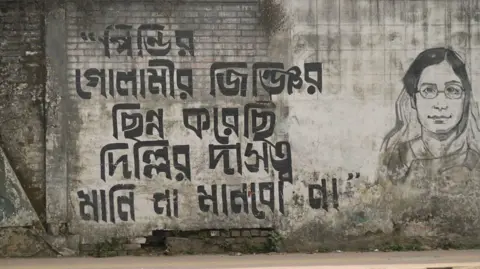

The walls of Dhaka University are screaming again.

Graffiti – angry, witty, sometimes poetic – sprawls across walls and corridors, echoing the Gen Z-led July 2024 uprising that toppled Sheikh Hasina after 15 years in power. Once Bangladesh’s pro-democracy icon, critics say she had grown increasingly autocratic. After her resignation, she fled to India.

Students gather in knots, debating politics. On an unkempt lawn, red lanterns sway above a modest Chinese New Year celebration – a small but telling detail in a country where Beijing and Delhi are both vying hard for influence. For many here, the election scheduled for 12 February will be their first genuine encounter with the ballot box.

Nobel peace-prize laureate Muhammad Yunus took charge days after Sheikh Hasina’s fall. Hasina now lives in exile in Delhi, which has refused to return her to face a death sentence imposed in absentia over the brutal security crackdown in 2024 – violence in which the UN says around 1,400 people were killed, mostly by security forces.

Her Awami League – the country’s oldest party, which commanded some 30% of the popular vote – has been barred from contesting. Analysts say the main opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) is now moving to occupy the liberal-centrist space it has vacated. The main Islamist party, Jamaat-e-Islami, has joined forces with a party born out of the student uprising.

But the slogans on the campus – and beyond – are not only about democracy at home. It increasingly points across the border.

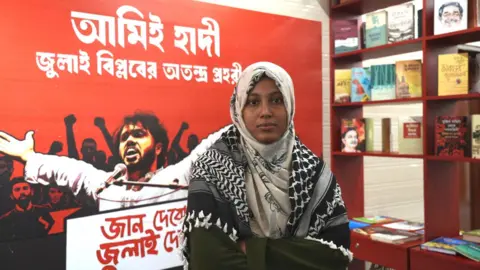

“Dhaka, not Delhi” is splashed on walls – and stitched onto saris, a traditional dress for women in South Asia. Among the young, “hegemony” has slipped into everyday speech, shorthand for India’s long shadow over Bangladesh.

Anahita Sachdev/BBC

Anahita Sachdev/BBC

“The young generation feels India has been intervening in our country for many years,” says Mosharraf Hossain, a 24-year-old sociology student. “Especially after the 2014 election, which was basically a one-party election.”

That grievance – Delhi’s perceived role in enabling Bangladesh’s democratic erosion – sits at the heart of a sharp rise in anti-Indian sentiment. The result: India-Bangladesh relations, once touted as a model of neighbourhood diplomacy, are now at their lowest ebb in decades.

“Delhi is struggling in Dhaka because of deep anti-India sentiment in Bangladesh and a hardening, often a hostile turn, in India’s own domestic political discourse towards its neighbour,” says Avinash Paliwal, who teaches politics and international studies at SOAS University of London.

Many blame Delhi for supporting an increasingly authoritarian Hasina in her final years and see India as an overbearing neighbour. They remember disputed general elections in 2014, 2018 and 2024 and Delhi’s “endorsement” of them.

“India supported Hasina’s regime without any pressure, without any questions,” Hossain says. “People think the destruction of democracy was supported by India.”

That sense of betrayal has merged with longer-standing grievances – border killings, water-sharing disputes, trade restrictions and inflammatory rhetoric from Indian politicians and television studios – into a more corrosive belief: that India views Bangladesh less as a sovereign equal than as a pliant backyard.

Local media is rife with reports that an Indian conglomerate supplying electricity to Bangladesh has been cheating the country – a charge the group denies. On Facebook, a key platform for political mobilisation, campaigns rage to ban a leading daily branded an “Indian agent”. Both countries have suspended most visa services.

Delhi’s decision to bar a Bangladeshi cricketer from the Indian Premier League (IPL) and refusal to move Bangladesh’s T20 World Cup matches from India to Sri Lanka has fed resentment across the border.

REUTERS

REUTERS

“To be sure, India has channels with all stakeholders in Bangladesh. But translating such engagement into positive political outcomes remains challenging in the current political climate,” says Paliwal.

Delhi has indeed begun to broaden its outreach.

Last month Foreign Minister S Jaishankar travelled to Dhaka for former prime minister and Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) leader Khaleda Zia’s funeral, and used the occasion to meet the party’s acting chairman Tarique Rahman. The 60-year-old heir to the Zia dynasty, Rahman recently returned after 17 years in exile in London and now looms as the frontrunner in the landmark election.

India has also opened channels to Islamist forces. A senior Jamaat-e-Islami leader told me that Indian officials have engaged the party’s leadership four times in the past year, including a recent invitation to the Indian High Commission’s Republic Day reception in a Dhaka hotel.

Yet these tactical shifts have done little to arrest the broader slide. Kamal Ahmed, consulting editor of The Daily Star newspaper, says the current chill marks a low unseen even during earlier crises. “There’s no doubt this is the lowest point of the bilateral relationship,” he told the BBC.

The contrast with the Sheikh Hasina years is stark.

Over 17 years, Dhaka “opened up almost all fronts for India” – security co-operation, transit, trade, cultural exchange and people-to-people ties. Today, Ahmed says, “nothing is moving – neither people nor goodwill”.

Anahita Sachdev/BBC

Anahita Sachdev/BBC

What appears to have turned scepticism into anger was Delhi’s response after Hasina was ousted last August. Many Bangladeshis said they expected India to recalibrate a Bangladesh policy that had rested almost entirely on backing one party. Instead, India appeared to double down – offering Hasina refuge and tightening visa and trade restrictions. The message received in Dhaka, Ahmed says, was: Bangladeshis were “not being valued as neighbours”.

Rhetoric has worsened matters.

When Indian politicians label Bangladeshi migrants “termites” or talk of teaching Bangladesh a lesson “like Israel did in Gaza,” Ahmed asks: “How do you expect people in Bangladesh to react?”

Cultural retaliation followed – calls to boycott Indian goods, the suspension of IPL broadcasts – driven by resentment. “Culture, trade, respect – nothing is one-way traffic,” Ahmed says. “Unfortunately, that’s how the current Indian leadership is practising it.”

Yet officials in Dhaka caution against reading the relationship solely through its crises.

Shafiqul Alam, press secretary to Yunus, describes ties with India as “multi-dimensional”, anchored in geography as much as politics. “We share 54 rivers… We share language, we share the same history,” he says, citing trade flows and daily movement across a 4,096km (2,545-mile) frontier.

Even so, Alam admits public sentiment has hardened sharply.

Ask Bangladeshis why they could not vote freely for over 15 years, he says, and many give the same answer: Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarianism – and India’s “backing” of it. “They also say that Hasina has always been supported by India.”

Hasina’s flight to India after the 2024 violence remains an especially sore point.

Reuters

Reuters

“Hundreds of young people were killed… and then she fled to India,” Alam says. The perception that she was treated as a “head of a government”, rather than a disgraced leader, deepened anger.

Alam also criticises Indian media coverage as alarmist, dismissing claims of systematic persecution of minority Hindus as “a massive disinformation campaign”. Isolated incidents do occur, he says, but are routinely portrayed as religious violence. “Come and visit,” he urges Indian journalists. “Meet the people and see what actually happened.”

India, meanwhile, says independent sources have documented more than 2,900 incidents of violence against minorities – including killings, arson and land grabs -during the interim government’s tenure, adding that these cannot be all “media exaggeration or dismissed as political violence”.

Ali Riaz, an academic who is currently serving as the special assistant to Yunus, believes the rupture runs deeper than miscommunication.

ANAHITA SACHDEV/BBC

ANAHITA SACHDEV/BBC

“It has reached the bottom,” he says. He believes that over time, the relationship narrowed down to “a relationship between a party or an individual and the Indian establishment, rather than between Bangladesh and India”.

Long-standing disputes amplified the damage. Water sharing, Riaz argues, creates hierarchy. “If you control the water, the relationship immediately becomes unequal.”

Border killings cut deeper still. “It is viewed as how the Indian establishment see the lives of Bangladeshis.” India has denied unlawful killings by its forces in specific deaths along the border.

These issues, analysts say, are not episodic irritants but symbols of imbalance.

That imbalance, critics argue, was reinforced after Hasina’s fall. Mohammad Touhid Hossain, foreign affairs adviser to Yunus, says India failed to recalibrate, missing a chance to reset ties with the interim government. “We tried to go forward on a number of occasions, but then the response from India was on again, off again,” he told me.

India, for its part, has voiced concern over Bangladesh’s “deteriorating security environment” and called for “free, fair, inclusive and credible elections” conducted peacefully.

Political strain is now spilling into economic ties. Bilateral trade of $13.5bn could be far higher if tariff and non-tariff barriers were eased and diplomatic relations improved, says Fahmida Khatun of the think tank Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). “Political tension has led to economic tension.”

Yet this hardening at the state level does not always translate neatly on the street.

“Whenever I hear India, I think it is my enemy,” says Fatima Tasnim Juma of Inquilab Mancha, a cultural platform known for its nationalist anti-India messaging.

“But when it comes to people, it does not work like that.” Juma says she grew up in a Hindu-majority area; relatives move easily across the border. “Our conflict is with the Indian government or the structure. Not with people.”

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Anti-Indianism has been notably subdued on the campaign trail – not because it has faded, but because every political contender knows that a reset with India is unavoidable.

Even so, repairing India–Bangladesh ties will not be quick – or cosmetic.

“A reset won’t be easy simply because there’s an election or a new government. The background [issues] will remain,” says Alam.

Still, the rupture is not irreversible. “No state relationship is,” says Riaz – but the burden of repair, he argues, lies largely with Delhi and will require moving beyond the habit of managing Dhaka through favoured intermediaries. Ahmed says Bangladesh is open to normalising ties, but India needs a reset that works with whoever holds power in Dhaka.

Political figures frame the reset in moral as much as strategic terms.

Mahdi Amin, a key adviser to BNP leader Rahman, puts it bluntly: “The bigger the nation, the more the responsibility.”

People-to-people ties, he argues, can only grow if India aligns its policy with the aspirations of Bangladeshis, not just the preferences of governments.

Jamaat-e-Islami’s assistant general secretary Ahsanul Mehboob Zubair offers a cautious echo: “If those in charge in both countries act with sincerity, accept present realities, and treat each other with mutual respect and dignity, a constructive relationship is possible.”

That space for repair still exists – and a new government could make a difference.

“The current situation is more than a diplomatic chill, and less than a structural break,” notes Paliwal.

“Geography, history, and shared cultural heritage means that India and Bangladesh cannot wish away each other.”