Israeli prisons have become overwhelmed with the number of Palestinian detainees doubling to about 10,000 since October

Paul Adams

Diplomatic correspondent, Jerusalem

Warning: This article contains details which some readers may find upsetting

Israel’s leading human rights organisation says conditions inside Israeli prisons holding Palestinian detainees amount to torture.

B’tselem’s report entitled “Welcome to Hell”, contains testimony from 55 recently released Palestinian detainees, whose graphic testimony points to a dramatic worsening of conditions inside prisons since the start of the Gaza war 10 months ago.

It’s the latest in a series of reports, including one last week by the UN, which contain shocking allegations of abuse directed against Palestinian prisoners.

B’tselem says the testimony their researchers have gathered is remarkably consistent.

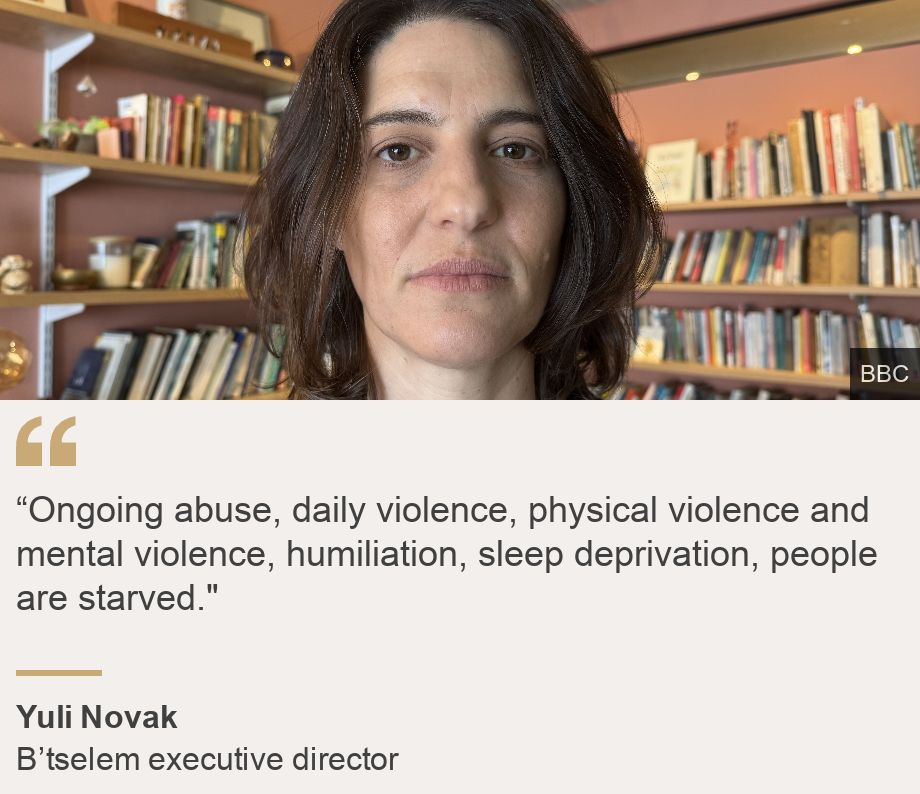

“All of them again and again, told us the same thing,” says Yuli Novak, B’tselem’s executive director.

“Ongoing abuse, daily violence, physical violence and mental violence, humiliation, sleep deprivation, people are starved.”

Ms Novak’s conclusion is stark.

“The Israeli prison system as a whole, in regard to Palestinians, turned into a network of torture camps.”

‘Overcrowded, filthy cells’

Since the deadly Hamas attacks of 7 October, in which around 1,200 Israelis and foreign nationals were killed, the number of Palestinian detainees has doubled to around 10,000.

Israel’s prisons – some run by the army, others by the country’s prison service – have become overwhelmed.

Jails are overflowing, with a dozen or more inmates sometimes sharing cells designed to accommodate no more than six.

B’tselem’s report describes overcrowded, filthy cells, where some inmates are forced to sleep on the floor, sometimes without mattresses or blankets.

Some prisoners were captured in the immediate aftermath of the Hamas attacks. Others were rounded up in Gaza as Israel’s invasion got under way, or were arrested in Israel or the occupied West Bank.

Many were later released without charge.

Firas Hassan says “life totally changed” for him as a prisoner in an Israeli jail after the 7 October attacks

Firas Hassan was already in jail in October, held under “administrative detention”, a measure by which suspects – though it has overwhelmingly been applied to Palestinians – can be detained, more or less indefinitely, without charge.

Israel says that its use of the policy is necessary, and compliant with international law.

Firas says he saw with his own eyes how conditions quickly deteriorated after 7 October.

“Life totally changed,” he told me when we met in Tuqu’, a West Bank village south of Bethlehem.

“I call what happened a tsunami.”

Mr Hassan has been in and out of jail since the early nineties, twice charged with membership of Palestinian Islamic Jihad, an armed group designated as a terrorist organisation by Israel and much of the West.

He makes no secret of his past affiliation, saying he was “active”.

Familiar with the rigours of life in prison, he said nothing prepared him for what happened when officers entered his cell two days after 7 October.

“We were severely beaten by 20 officers, masked men using batons and sticks, dogs and firearms,” he said.

“We were tied from behind, our eyes blindfolded, beaten severely. Blood was gushing from my face. They kept beating us for 50 minutes. I saw them from under the blindfold. They were filming us while beating us.”

Mr Hassan was eventually released, without charge, in April, by which time he said he had lost 3 stone (20kg).

A video filmed on the day of his release shows a gaunt figure.

“I spent 13 years in prison in the past,” he told B’tselem researchers later that month, “and never experienced anything like that.”

Sari Khourieh, an Israeli Arab, says there was no law or order inside the northern Israeli prison where he was held for 10 days

But it’s not just Palestinians from Gaza and the West Bank who talk about the abuse in Israeli prisons.

Israeli citizens, like Sari Khourieh, an Israeli Arab lawyer from Haifa, say it has also happened to them.

Mr Khourieh was held at the Megiddo prison in northern Israel for 10 days last November. The police said that two of his Facebook posts had glorified the actions of Hamas – a charge quickly dismissed.

But his brief experience of prison – his first – nearly broke him.

“They just lost their mind,” he says of the scenes he witnessed at Megiddo.

“There was no law. There was no order inside.”

Mr Khourieh says he was spared the worst of the abuse. But he says he was stunned by the treatment of his fellow inmates.

“They were hitting them badly for no reason,” he told us. “They were screaming, the guys, ‘we didn’t do nothing. You don’t have to hit us.’”

Speaking to other detainees, he quickly learned that what he was seeing was not normal.

“It wasn’t the best treatment before 7 October, they told me, but afterwards everything was different.”

During a brief spell in an area of isolation cells known by the prisoners as Tora Bora (a reference to al-Qaeda’s network of caves in Afghanistan), Mr Khourieh says he heard a beaten inmate pleading for medical help in an adjacent cell.

According to Mr Khourieh, doctors tried to revive him, but he died shortly afterwards.

BBC

“Ongoing abuse, daily violence, physical violence and mental violence, humiliation, sleep deprivation, people are starved.”

According to last week’s UN report, “announcements by IPS (Israel Prison Service) and prisoners organisations indicate that 17 Palestinians have died in the custody of the IPS between 7 October and 15 May”.

Israel’s military advocate, meanwhile, said on 26 May that it was investigating the deaths of 35 Gaza detainees in army custody.

Several months after Mr Khourieh’s release – again, without charge – the lawyer is still struggling to make sense of what he witnessed at Megiddo.

“I’m an Israeli…I’m a lawyer,” he told us. “I’ve seen the world outside the prison. Now I’m inside. I see another world.”

His faith in citizenship and the rule of law, he says, has been shattered.

“It was all crushed after this experience.”

We put claims of the widespread mistreatment of Palestinian detainees to the authorities involved.

The army said it “rejects outright allegations of systematic abuse of detainees”.

“Concrete complaints regarding misconduct or unsatisfactory conditions of detention,” the army told us, “are forwarded to relevant bodies in the IDF, and are dealt with accordingly.”

The prison service said it “was not aware of the claims you described, and as far as we know, no such events have occurred”.

Image source, Channel 13

The Israeli Prison Service denies the allegations of abuse, saying “no such events have occurred”

Since 7 October, Israel has refused to grant the International Committee of the Red Cross access to Palestinian detainees, as international law requires.

No explanation has been given for this refusal, but the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has frequently expressed its frustration over the ICRC’s failure to gain access to Israeli and other hostages being held in Gaza.

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI) has accused the government of “consciously defying international law”.

Last week, the treatment of Palestinian prisoners ignited a furious public row, as far right demonstrators – including members of Israel’s parliament – violently tried to prevent the arrest of soldiers accused of sexually abusing a prisoner from Gaza at the Sde Teiman military base.

Some of those protesting were followers of Israel’s hardline security minister, Itamar Ben Gvir, the man in overall charge of the prison service.

Mr Ben Gvir has frequently boasted that under his watch, conditions for Palestinian detainees have deteriorated sharply.

“I’m proud that during my time we changed all the conditions,” he told members of Israel’s parliament, the Knesset, during a rowdy session in July.

For B’Tselem, Mr Ben Gvir bears a heavy responsibility for the abuses now being reported.

“These systems were put in the hands of the most right wing, most racist minister that Israel ever had,” Yuli Novak told us.

For her, Israel’s treatment of prisoners, in the wake of the traumatic events of 7 October, is a dangerous indicator of the nation’s moral decline.

“The trauma and anxiety walks with us each and every day,” she says.

“But to let this thing turn us into something that it not human, that doesn’t see people, I think is tragic.”