From one to 29 medals: India’s Paralympic revolution

Navdeep Singh won a gold medal in the men’s javelin throw

Vikas Pandey

BBC News, Delhi

India had a lone shining moment at the 2012 London Paralympics when Girisha Hosanagara Nagarajegowda won a silver medal in the men’s high jump.

The country hadn’t won any medal at the 2008 edition in Beijing, so it felt special to millions of Indians.

But Nagarajegowda’s win also sparked discussions on whether a lone medal was enough for a country that has millions of people with disabilities.

It also raised questions around India’s attitudes to para sport and disability in general. But something seems to have clicked for the country since 2012.

India won four medals in Rio in 2016 and 20 at the 2020 Tokyo Paralympics.

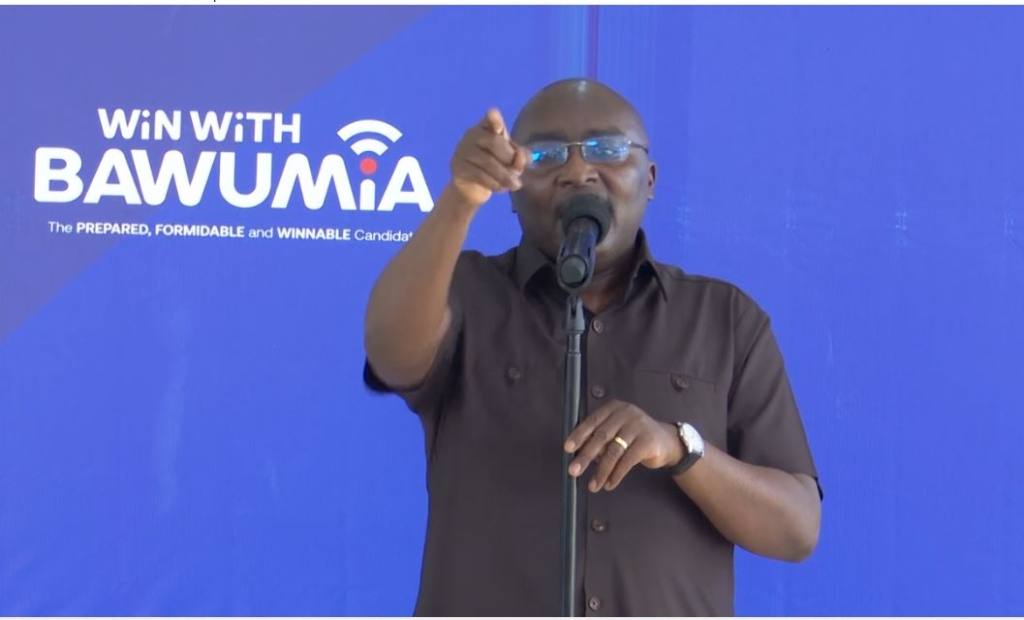

And it closed the Paris Paralympics with an impressive tally of 29 medals. There have been so many moments to savour for India in Paris – from Sheetal Devi, who competes without arms, winning a bronze with Rakesh Kumar in a mixed compound archery event to Navdeep Singh registering a record throw of 47.32m in javelin to win a gold in the F41 category (athletes with short stature compete in this class).

Image source, Getty Images

Champion shooter Avani Lekhara became the first Indian woman to win two Paralympic gold medals

These achievements are special given the leap of growth Indian para athletes have shown in just over a decade.

India still has a long way to go to take on countries like China (220 medals), Great Britain (124) and the US (105) but supporters of para sports in the country say the tide may be turning.

So what changed in this relatively short period of time?

Plenty.

Several government agencies, coaches and corporate firms came together to invest in para athletics.

And as they helped more heroes emerge, more children and their parents felt confident to take up para sport as a profession.

Gaurav Khanna, the head coach of the Indian para badminton team, says having people to look up to has changed mindsets:

“This has increased the number of athletes who are participating and who are having confidence that they can do better. When I joined the para badminton team in 2015, there were only 50 athletes in the national camp. Now that figure has gone up to 1,000.”

Image source, Getty Images

Nishad Kumar won the silver medal in the men’s high jump

This is a stark change from the time he began training para athletes. Earlier, Khanna used to spot young talent in strange places like shopping malls, corner shops and even on roads while driving in the country’s rural areas.

“It used to be tough to convince parents to send their children for something they knew little about. Just imagine convincing the parents of a young girl to send her to a faraway camp and trust somebody they didn’t know. But that’s how earlier champions came to the fore,” he adds.

Technology has also played a crucial part. With India’s growing economic prowess, Indian para athletes now have access to world-class equipment.

Khanna says each category in different disability sports requires specific equipment, which is often designed to meet the needs of an individual athlete.

“We didn’t have access to good equipment earlier and we used whatever we could get. But now it’s a different world for our athletes,” he says.

Image source, Getty Images

Archer Sheetal Devi, 17, became India’s youngest Paralympic medallist

Disability rights activist Nipun Malhotra also acknowledges the change in mindset. He says the biggest change he has noticed is that parents now believe that children with disabilities can also become heroes:

“I think families have started playing a much more important role, and people with disabilities have got integrated much more into families today than they were 20 years ago. This also affects how society looks at disability as well. The fact that there are people with disabilities who are excelling in sports also gives hope to the future generations.”

Khanna and Malhotra both give credit to government schemes like TOPS (Target Olympic Podium Scheme) for identifying and supporting young talent.

Private organisations like the Olympic Gold Quest, which is funded by corporate houses, have also helped para athletes realise their full potential.

And then there are people like Khanna who started talent scouting and coaching using their own money, and continue to do so.

Image source, Getty Images

Yogesh Kathuniya won the silver medal in the men’s discus throw

Sheetal Devi’s journey wouldn’t be possible without the support she got from a private organisation. Born in a small village in Jammu district, she didn’t know much about archery until two years ago.

She visited the Shri Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine Board sports complex in Jammu’s Katra on a friend’s advice and met her coach Kuldeep Vedwan there.

Now she is as popular in India as Manu Bhaker, who won two bronze medals in shooting at the Paris Olympics.

Brands are already lining up to sign Devi, and a jewellery advert featuring her has gone viral.

Social media has helped para athletes connect with people directly and tell them their stories. Experts hope that this will help them build a brand and eventually take them to commercial success as well. Stars like Devi are already there and there is hope that many more will follow.

Image source, Reuters

Deepthi Jeevanji won a bronze medal in the women’s 400m

But there is plenty of work left to do.

India has a long way to go to become disability-friendly, with most public places still lacking basic facilities to help people navigate everyday life.

Malhotra, who was born with arthrogryposis – a rare congenital disorder that meant that the muscles in his arms and legs didn’t fully develop – found that many didn’t want to hire him despite his degree in economics from a prestigious college in India.

He hopes the triumph of India’s para athletes will slowly help in opening those shut doors.

“The upside of this [India’s medal tally in Paris] is pretty high. Disabled people, including those with degrees from Oxford, struggle to get jobs in India. What our Paralympics triumph will do is that it will open the minds of employers about employing disabled people without any fear,” he says.

Image source, Getty Images

Harvinder Singh got India its first-ever Para archery gold

While India’s impressive showing in Paris has delighted many, coaches like Khanna believe grassroots facilities for para athletes are still poor even in big Indian cities.

He points out that classifications in para sports are very technical and trained coaches are essential to identify raw talent and guide them towards the right categories – all this even before a young person can start training.

Sports facilities have improved drastically even in small Indian cities in the past two decades but para sport still lags behind by quite a distance.

“You will not find well-trained para sport coaches even in most prominent schools in cities like Delhi and Mumbai and this has to change,” says Malhotra.

Image source, Getty Images

Nitesh Kumar pulled off a stunning victory to win the gold medal in the men’s singles badminton

For Khanna, change has to start at entry level and he urges government and private players to train more coaches.

He argues that players can hope for stardom today only if they are spotted and then supported by organisations.

“But we won’t get to the top of the table like this. We have to ensure that a disabled child even in the remotest part of the country should have access to a good coach and facilities,” the para badminton coach adds.