Introduction to Vacant Dwellings

Vacant dwellings have become a growing issue worldwide, influenced by factors such as urbanisation, economic downturns, real estate speculation, and demographic shifts.

In developed nations, large cities often experience high vacancy rates due to investment properties remaining unoccupied, housing affordability crises, or declining populations in certain areas.

Countries like the United States, China, and Japan have notable cases of vacant housing—China’s “ghost cities” and Japan’s “akiya” (abandoned homes) are prime examples.

Meanwhile, in parts of Europe, depopulated rural areas suffer from increasing vacant dwellings due to urban migration. Addressing housing vacancies has become a key challenge for policymakers seeking to ensure optimal housing use and prevent urban decay.

Vacant Dwellings in Africa

Africa’s vacant dwelling trends are shaped by rapid urbanisation, economic instability, and infrastructure gaps.

Major cities like Lagos, Nairobi, and Johannesburg have seen significant growth in vacant luxury apartments and high-rise buildings, which are unaffordable for the majority of the population.

Meanwhile, rural areas across the continent face housing vacancies due to migration to urban centres in search of better opportunities.

The lack of formal housing policies and unregulated real estate markets often lead to the construction of properties that remain unoccupied due to price mismatches or poor planning. Addressing housing vacancies in Africa requires a balance between affordable housing initiatives and strategic urban planning.

Vacant Dwellings in Ghana

In Ghana, vacant dwellings reflect broader urbanisation and housing market trends. Urban centres, especially in the Greater Accra and Ashanti regions, have a high concentration of vacant houses, largely due to rapid real estate development and affordability challenges.

Many newly built houses remain unoccupied as they cater to high-income groups, while middle- and low-income earners struggle with housing shortages. On the other hand, some rural areas experience vacant dwellings due to migration to urban centres for employment opportunities, leaving behind underutilised housing.

Data on vacant housing in Ghana highlights the need for balanced housing policies, affordable housing projects, and sustainable urban planning to ensure optimal use of available housing stock and reduce the mismatch between supply and demand.

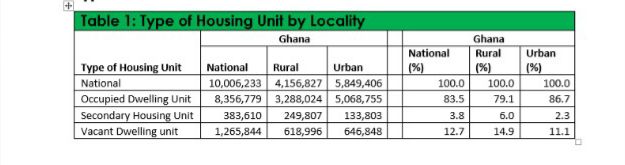

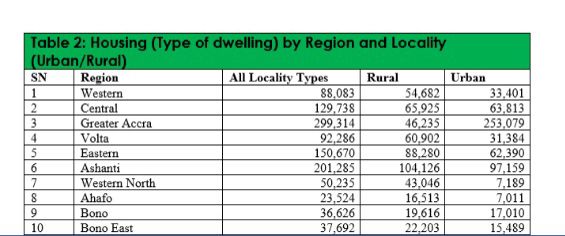

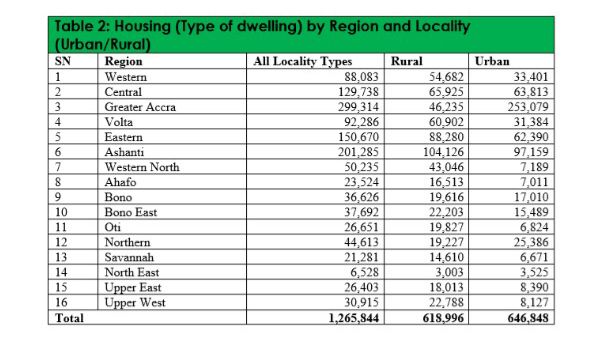

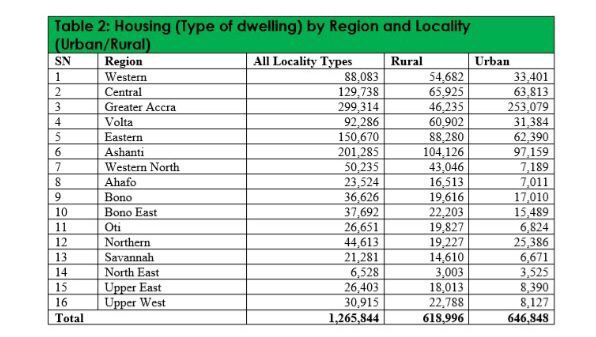

Tables in Appendix 1 provide a detailed breakdown of housing types across different geographic areas in Ghana, categorised by locality: All Locality Types, Rural, and Urban. The data reveals significant variations in housing distribution across the regions.

Percentage of Vacant dwelling unit by region and locality (Urban/Rural)

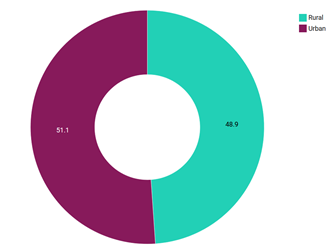

The national percentage of vacant dwelling units is 12.7 percent, with 51.1 percent of these located in urban areas and 48.9 percent in rural areas. Urban areas have a higher share of vacant dwellings, aligning with trends of rapid urbanization, increased real estate development, and potentially unaffordable housing.

Out of the 12 percent of vacant dwelling in Ghana Greater Accra (23.6%) has the highest percentage of vacant dwellings, with a significantly larger proportion (39.1% urban vs. 7.5% rural).

Ashanti (15.9%) follows, with a relatively balanced split (16.8% rural vs. 15.0% urban).

Western (7.0%), Volta (7.3%), and Western North (4.0%) show a trend where rural areas have a higher percentage of vacant dwellings than urban areas. Savannah (1.7%) and North East (0.5%) have the lowest overall vacancy rates.

Greater Accra exhibits the highest number of dwellings in urban areas (253,079), reflecting its status as the capital and a major economic hub, while also having a substantial number of dwellings across all locality types (299,314). Ashanti follows with a significant number of dwellings in all locality types (201,285), with a more balanced distribution between rural (104,126) and urban (97,159) areas, indicating a blend of urban and rural development.

Central, Eastern and Western regions also show substantial housing numbers, with Central having 129,738 dwellings in all locality types, Eastern having 150,670, and Western having 88,083. Volta shows a higher concentration in rural areas (60,902) compared to urban (31,384), indicating a more agrarian lifestyle in the region.

Regions like Western North, Ahafo, Bono, Bono East, Oti, Savannah and North East have relatively lower housing numbers across all categories, reflecting smaller populations and potentially less developed infrastructure. Notably, North East has the lowest figures, with only 6,528 dwellings in all locality types.

Overall, the data underscores the disparities in housing distribution between urban and rural areas across Ghana. The total number of dwellings in all locality types is 1,265,844, split between 618,996 in rural areas and 646,848 in urban areas, highlighting a slight urban dominance in housing. This analysis is crucial for policymakers and urban planners to address housing needs and infrastructure development in different regions of Ghana.

The national percentage of vacant dwelling units stands at 12.7%, with 51.1% of these located in urban areas and 48.9% in rural areas. Urban areas have a higher share of vacant dwellings, reflecting trends of rapid urbanisation, increased real estate development, and potentially unaffordable housing.

Of the 12% of vacant dwellings in Ghana, Greater Accra (23.6%) has the highest percentage of vacant properties, with a significantly larger proportion in urban areas (39.1%) compared to rural areas (7.5%). Ashanti (15.9%) follows, with a relatively balanced split between rural (16.8%) and urban (15.0%) areas.

The Western (7.0%), Volta (7.3%), and Western North (4.0%) regions show a trend where rural areas have a higher percentage of vacant dwellings than urban areas. The Savannah (1.7%) and North East (0.5%) regions have the lowest overall vacancy rates.

Greater Accra exhibits the highest number of dwellings in urban areas (253,079), reflecting its status as the capital and a major economic hub, while also having a substantial number of dwellings across all locality types (299,314). Ashanti follows with a significant number of dwellings in all locality types (201,285), with a more balanced distribution between rural (104,126) and urban (97,159) areas, indicating a blend of urban and rural development.

The Central, Eastern, and Western regions also show substantial housing numbers, with Central having 129,738 dwellings across all locality types, Eastern having 150,670, and Western having 88,083. Volta shows a higher concentration of dwellings in rural areas (60,902) compared to urban (31,384), suggesting a more agrarian lifestyle in the region.

Regions such as Western North, Ahafo, Bono, Bono East, Oti, Savannah, and North East have relatively lower housing numbers across all categories, reflecting smaller populations and potentially less developed infrastructure. Notably, North East has the lowest figures, with only 6,528 dwellings across all locality types.

Overall, the data highlights the disparities in housing distribution between urban and rural areas across Ghana. The total number of dwellings in all locality types is 1,265,844, with 618,996 in rural areas and 646,848 in urban areas, reflecting a slight urban dominance in housing. This analysis is essential for policymakers and urban planners to address housing needs and infrastructure development in different regions of Ghana.

Vacant dwelling Unit by Locality (Urban/Rural)

The vacant dwelling units are almost evenly split between rural and urban areas, with urban areas accounting for 51.1% of the vacant dwellings, compared to 48.9% in rural areas.

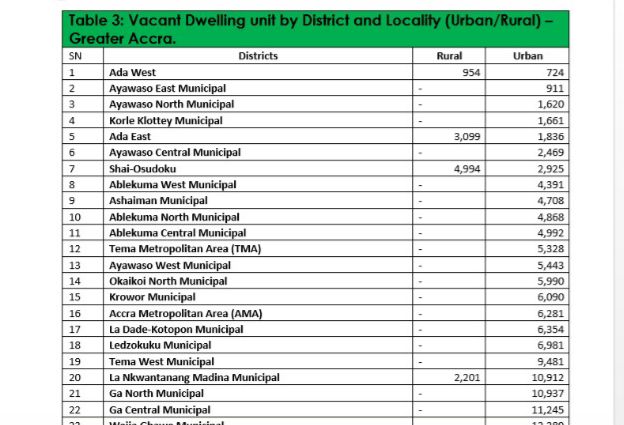

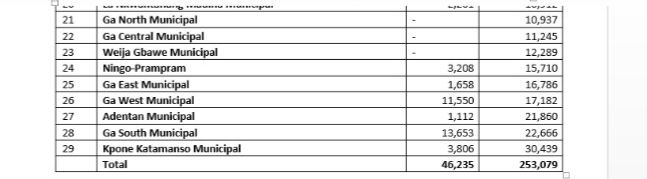

Table 3 (see Appendix 1) presents data on vacant dwelling units across various districts, categorised by rural and urban locations. The data reveals significant disparities in the distribution of vacant housing units, highlighting trends of urbanisation and regional development differences.

Districts such as Ada West and Ada East show a mix of rural and urban vacant dwellings, with Ada East having a notable 3,099 rural vacant units and 1,836 urban units, suggesting a significant rural presence. Shai-Osudoku also follows this trend with 4,994 rural and 2,925 urban vacant units. Ningo-Prampram, Ga East Municipal, Ga West Municipal, Adentan Municipal, Ga South Municipal, and Kpone Katamanso Municipal also display a mix of rural and urban vacant dwellings.

In contrast, many districts, particularly those within the Accra Metropolitan Area (AMA) and surrounding municipalities like Ayawaso East, North, and Central, Ablekuma West, North, and Central, Tema Metropolitan Area (TMA), Okaikoi North, Krowor, La Dade-Kotopon, Ledzokuku, Tema West and Ga North, show no vacant dwelling units in rural areas, indicating a strong urban concentration.

The districts with the highest numbers of vacant urban dwelling units are Kpone Katamanso Municipal (30,439), Ga South Municipal (22,666), Adentan Municipal (21,860), Ga West Municipal (17,182), Ga East Municipal (16,786), and Ningo-Prampram (15,710), reflecting rapid urbanisation and potentially higher rates of new construction or unoccupied properties in these areas. La Nkwantanang Madina Municipal also shows a significant number of urban vacant units (10,912).

Overall, the total number of vacant dwelling units is 46,235 in rural areas and 253,079 in urban areas, underscoring a substantial urban-rural divide. This distribution highlights the ongoing urbanisation trend in Ghana, with more vacant housing units concentrated in urban centres.

This analysis is crucial for urban planners and policymakers to understand housing dynamics, address housing shortages, and manage urban sprawl. The data suggests a need for targeted housing policies that consider the unique characteristics of both rural and urban areas, promoting balanced regional development and addressing the specific housing needs of different districts. Further investigation into the reasons for vacant dwellings, such as affordability, infrastructure, and economic opportunities, would provide additional insights for effective housing strategies.

Conclusion:

The data highlights significant disparities in housing distribution between rural and urban areas across Ghana. Urban areas, particularly in the Greater Accra and Ashanti regions, show a higher concentration of dwellings, reflecting economic development and urbanisation trends.

Conversely, regions such as Volta, North East, and other smaller regions exhibit a predominantly rural housing pattern, indicating agrarian lifestyles and lower urbanisation levels. The analysis of vacant dwelling units further reinforces the urban-rural divide, with urban areas having a significantly higher number of vacant units, potentially due to rapid urbanisation, new construction, or affordability issues.

Recommendations:

- Urban Housing and Infrastructure Development: Given the high concentration of dwellings in urban areas, policymakers should invest in infrastructure development, affordable housing schemes, and improved urban planning to accommodate growing populations.

- Balanced Regional Development: The government should implement policies that encourage rural development, including better infrastructure, job creation, and improved housing conditions, to reduce urban migration pressures.

- Vacant Housing Utilisation: Authorities should investigate the high number of vacant urban housing units to determine the underlying causes (e.g., affordability, ownership regulations, or infrastructure gaps) and create policies to optimise housing use.

- Data-Driven Housing Policies: Future housing strategies should be tailored to the specific needs of different regions, promoting equitable growth and sustainable housing development across both rural and urban areas.

- Sustainable Urban Planning: With increasing urbanisation, planners should ensure controlled expansion, efficient land use, and the integration of smart city solutions to manage urban sprawl effectively. By addressing these issues, Ghana can work towards a more balanced housing distribution, ensuring adequate infrastructure and sustainable development across all regions.

The writer, Victor Boateng Owusu is a senior Statistician at the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS)

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.