The world’s most important multilateral bank is punching below its weight

The turmoil sparked worldwide by the foreign aid freeze in the United States has all global development actors scrambling for gap-fillers and new sources of development finance.

In that sphere, few institutions are as important as the World Bank, especially in Africa. As finance ministers and other global economy actors gather in Washington DC for the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF, the focus shall be on how its unique role, mandate, and capabilities can be better harnessed for the unprecedented challenges confronting the world of global development.

When the pandemic revealed deep-seated vulnerabilities and threw some African economies like Ghana, Zambia, and Kenya into pandemonium, they all turned to the IMF for the obligatory rescue package. Since the IMF only offers acute relief, it was necessary for other donors to step in with longer-term financial recovery support. Only the World Bank could offer any meaningful sums.

Yet, this venerable institution is itself wrestling with some profound issues, issues that threaten its full potential.

In 2015, the world’s largest multilateral development finance institution worked alongside the United Nations to set 17 concrete targets for 2030, including helping to end poverty and hunger, supporting accountable governance, and tackling climate change worldwide. Not only is the world not on track to achieve these goals, in many regions, progress tackling poverty and corruption is backsliding.

Many outside the rarefied setting of development finance think the problem is just one of “more capital”. And, true, when the World Bank unveiled an “evolution roadmap” in 2022, the plan’s catchiest goal was to find more money to lend by optimising its balance sheet, loan structures, and financial instruments.

But the crisis confronting the World Bank, as many insiders and specialists know well enough, is much bigger than mobilising more capital. A clear-eyed look at the institution’s past twenty years reveals that the obstacles to its effectiveness loom larger than capital deficits. There are real gaps and bumps in places where even critics tend not to pay too much attention: the governance question in the member states receiving its loans and how its own oversight process may be begging the question. Previous capital increases led to an immediate rise in lending, but over time, as I hope to demonstrate, the effects of capital raises are blunted by other less notable factors.

Thanks to oversight issues at the bank and governance weaknesses in recipient countries, a very significant proportion of the funds the World Bank can deploy fail to reach those on the ground who need help the most. Of what does reach the ground, a non-trivial proportion is lost to mismanagement.

Ghana is a useful example: close scrutiny of even the projects the World Bank celebrates as successes reveal critical challenges that are often left unattended to due to the limitations of the World Bank’s auditing and remedial processes.

So long as these auditing and correctional limitations persist, opportunities for serious and extensive governance reforms to ensure that World Bank resources are maximised will be underused.

Introducing the constriction problem

As far as development lending is concerned, the World Bank has three main arms: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which obtains most of its money from the capital markets for on-lending; the International Development Agency (IDA), which is primarily funded by rich countries so that it can lend at the lowest rate possible to the poorest countries; and the International Finance Corporation, which focuses on the private sector, and thus won’t be discussed much in this essay.

On the back of its solid credit rating, the IBRD raises money to lend to governments that would, on their own, be considered too risky by the private markets. The premise that raising more money will correspond to an increase in useful loans has long guided World Bank strategy. In 2011, for instance, the IBRD boosted its capital by 31 percent, mostly by raising bonds. In 2018, it secured another significant capital boost of $7.5 billion in cash and $52.6 billion from the governments of rich countries in the form of callable capital, which is a kind of standby financing instrument. The World Bank described the result as “transformational.”

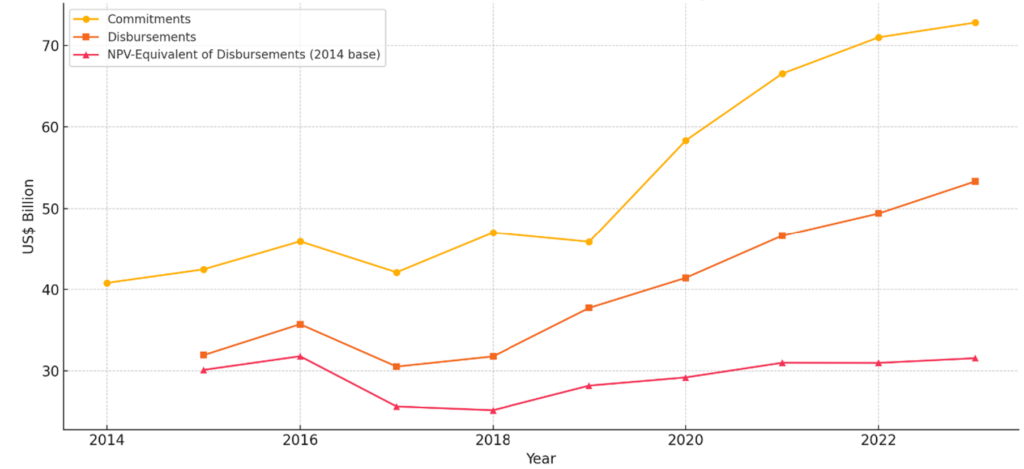

In the four years following the “unprecedented” capital raise in 2018 (i.e. from 2019 to 2022), the World Bank Group’s total lending allocations to borrowing countries, technically called “commitments”, went from $68 billion a year to $104 billion a year, partly due to the surge in pandemic-related funding. Compare this to the record in the four years before the capital increase (i.e. from 2015 to 2018), commitments could only increase by a mere $7 billion, from $60 billion to $67 billion.

In the general press, and among the public, the correlations have been taken to imply that the more capital the World Bank has, the more it can lend. Indeed, this is exactly how it was interpreted when in 2024 it vowed to deploy an extra $150 billion over the next ten years to sustain the trend of increasing lending commitments.

But as we have hinted already, things are not so straightforward. Since we are focused on the World Bank’s interactions with countries, we will limit the analysis to the IBRD and IDA. Because we are more concerned about money actually being deployed on the ground to transform lives, we should focus less on commitments and more on how much money the World Bank actually releases to governments, technically known as “disbursements”. Furthermore, in these fast-growing developing countries where the World Bank does most of its lending, a dollar in, say, 2022 has less value than in, say, 2015. That is to say, we must factor in the effects of inflation and what in economics is called the “time value of money” by using an appropriate “social discount rate”, which for our current purposes we shall peg at 6% (conservatively lower than the 10% to 12% typically used in the World Bank’s project appraisals in the developing world). We will refer to this measure as the “NPV equivalent” of the disbursement amounts.

With these technical minutiae out of the way, let’s review again the impact of capital increases and the ability of the World Bank to put money to work on the ground with our enhanced lens.

Whilst commitments have grown considerably in the wake of recent large capital increases, IBRD+IDA disbursements have seen less giddy growth, even in nominal terms (without accounting for time-value). In the years following the 2018 capital raise the figure went from roughly $37.7 billion in 2019 to roughly $49.4 billion in 2022. This is a little above half the growth rate of commitments. Applying the NPV lens is, however, how one can best appreciate the full extent of the stagnation. In NPV, or “real”, terms, disbursements considerably lag commitments between the 2019 and 2022 evaluation horizon.

The confusing gap between funds allocated to countries (“commitments”) and funds actually released for projects in those countries (“disbursements”) is, as we will show, significantly influenced by governance deficits.

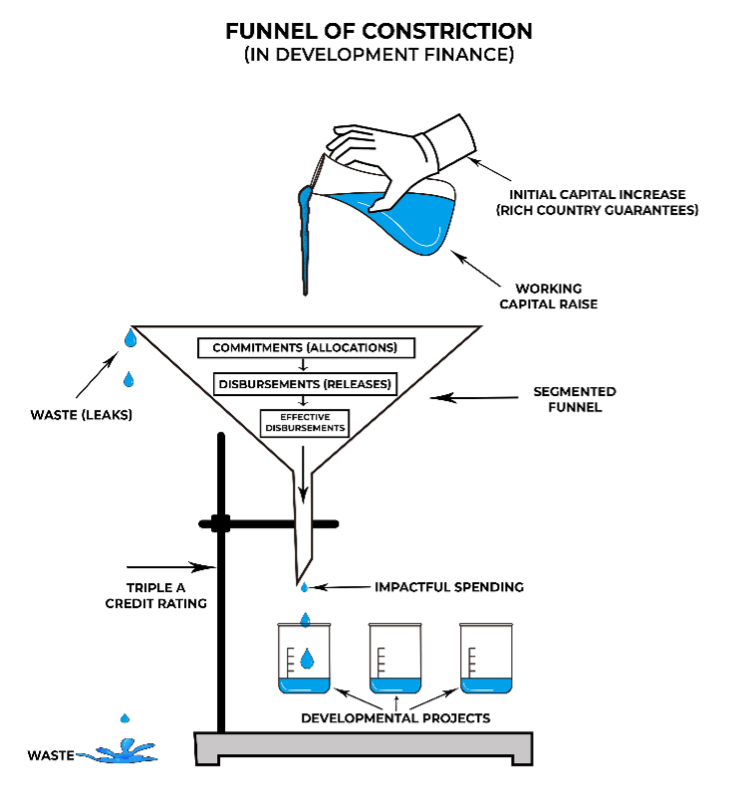

It starts by understanding how the World Bank finds the money that enables it to create commitments in the first place. A full 93% of its capital is in the form of implicit guarantees from rich countries on the back of which, bolstered by a solid credit rating, it sells bonds to private investors to raise virtually all the money it spends in countries. Only 7% of the institution’s equity is “paid-in capital”, or actual cash from its rich government shareholders. In theory, therefore, the World Bank’s ability to raise money is somewhat decoupled from the political shifts in the rich world and much more reliant on the capital markets. There is ample evidence to suggest that in a world where the World Bank had unlimited good projects to fund, it could raise nearly unlimited amounts of capital from the private sector. In the words of the World Bank, it has exceptional market access.

Why then does it always seem as though finding new money is the problem? In practice, the real bottleneck iis maintaining spending discipline at country-level to ensure that the World Bank’s money go into good projects. Preparing and supervising good projects through spending discipline is thus the starting point of dramatically expanding the amount of money it can reasonably raise whilst, at the same time, preventing risks to the World Bank’s own resources, and, implicitly, safeguarding its own triple A rating, or international capital market creditworthiness.

When translated into a bureaucratic process of operation, the process of enforcing spending discipline would inevitably create a gap between the loans pledges made to countries – its so-called commitments – and constrain how much money the World Bank can actually release based on the procedures and protocols necessary to maintain the integrity of its lending operations, and ultimately to sustain its exceptional market access.

Seeing as we should all be more concerned about monies actually released, and not just pledged, to countries by the World Bank, the percentage of commitments eventually disbursed (technically, the “disbursement ratio”) becomes a critical key performance indicator for the World Bank. In the four years before the momentous 2018 capital increase, the average IBRD+IDA disbursement ratio was 0.732 or 73.2%. That figure has remained stubbornly static for the next four years after the capital increase. In fact, at the end of the 4-year post-capital increase period, in 2022 to be precise, the disbursement ratio for Africa plummeted to 53% in West & Central Africa, a major focus of this essay, down from roughly 60% in 2018.

A disbursement rate of 60% or even 53% may not sound ominous until one realises that only a part of the story is being told. In more detailed investigations, we find that even funds released to a government may still not be spent, or could be mishandled in ways that forces the government to return them. The World Bank does not report comprehensively on such incidents. We can nonetheless assume that beyond the disbursement ratio, there is a more rigorous indicator which we may call, the “effective disbursement ratio”.

Thus, for example, in 2024, The World Bank insisted that about $32 million released in the past for water projects in Nigeria had been mishandled and out of this amount it insisted that 70% needed to be returned. Hence, if we were to be strict about things, we would not be referring to the disbursement ratio in the way the World Bank uses it as it does not provide a breakdown between gross and net amounts linked to such incidents, thereby complicating the analysis for all the various instances in which released monies still do not touch projects due to cancellations, returned funds, and other factors. We should be more focused on the “effective disbursement ratio” in order to properly gauge the scale of the challenge.

To be sure, country-level governance defects account for these gaps, but weaknesses in the World Bank’s own oversight and accountability mechanisms have contributed just as much to this disbursement – or more accurately, constriction – crisis.

Nearly two decades ago, a bewildered Milton Ayoki described the situation with respect to Uganda as follows:

“The country is facing power crisis and many factories and companies are operating at half capacity due to shortage of electricity. The government has often claimed that more power dams would be built if it had funds. And when funds are provided, it fails to utilise it.”

Years on, the confusion refuses to clear.

What is worse, in the global lender’s current governance milieu, improving disbursement rates can lead to waste, which then forces a slowdown in releases—a cycle illustrated in the image above. I call the phenomenon. “constriction.” It is a kind of reverse feedback mechanism that prevents sustained improvements in the disbursement ratio and a continuous uptick in effective disbursements.

Upon careful examination, we have found that the well-known Principal – Agent problem described in organisational theory applies. Governments and the World Bank engage in a cat-and-mouse game in which World Bank staff try to ensure enough adherence to programme standards to enable projects move along just well enough that they don’t become problem projects and even end up being cancelled.

A start-stop-start rollercoaster thus drags out projects as the government ramps up to meet a specific disbursement schedule, then backslides, recovers steam, backslides, and then repeat the cycle. From the point of view of the impartial observer, increasing disbursement rates appear to stockpile risks that materialise later in the form of various project failures. Disbursements are then throttled to deal with the problems. It is akin to a “compromise game” between donors and governments in which projects survive at the expense of coherent impact on the ground. From the standpoint of project beneficiaries, much of this manifests as “wasted resources” as I will show in a moment.

Again, Ghana is a valuable case study.

Constriction and the “compromise game” in Ghana

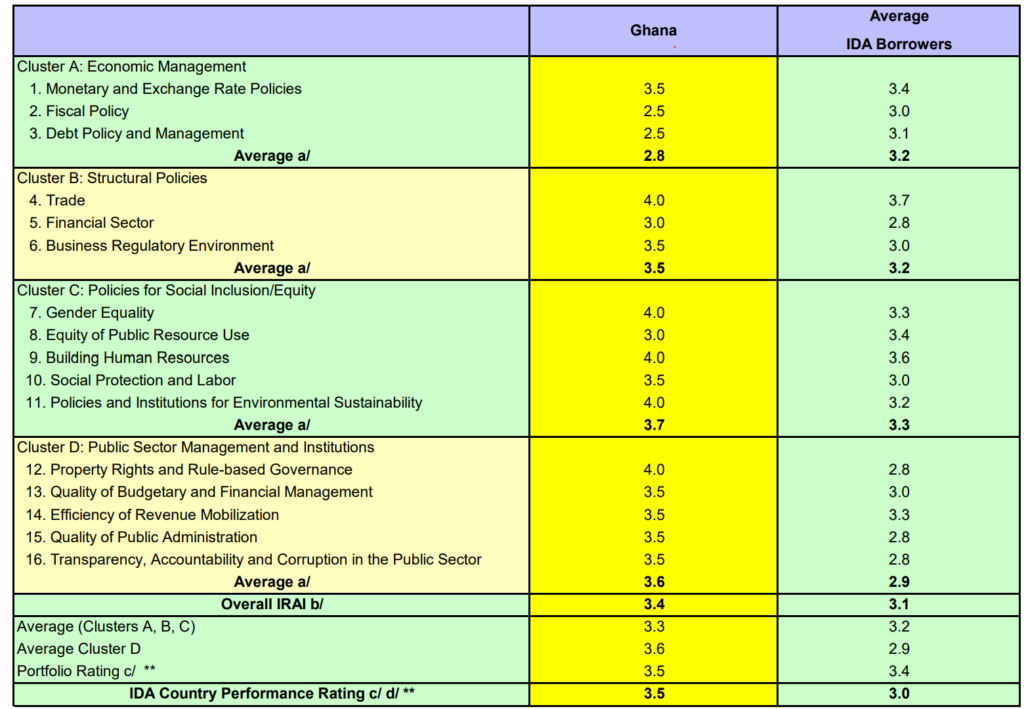

The World Bank uses a measure called the CPIA, or the Country Policy and Institutional Assessment, to grade countries’ governance capacity from a low of one to a high of six, and to rate their performance to determine how much IDA money they should be allocated.

Ghana’s CPIA score was 3.4 as of 2023, just above the Sub-Saharan average of 3.1. According to the World Bank’s own assessment framework, the country’s governance capacity thus reflects general trends across the continent.

Back in 2010, Ghana’s World Bank portfolio disbursement rate crashed to 5%, down from 30%. The World Bank tried to encourage disbursements through renewed pressure on the authorities, but these attempts ran up against a hard limitation: constriction. It was a bitter lesson in the truth that disbursement, unlike commitments, cannot simply be ramped up by force-feeding capital down the allocation tubes.

For a detailed study conducted for FDL, a think tank based in Paris, I analysed the World Bank’s portfolio of project loans to Ghana from 2010 to 2022, the same time-period used in the global disbursement analysis above, and selected a representative sample from its most highly rated projects. These were projects that were supposedly doing well.

Yet the results revealed some worrying undercurrents. In 2010, for instance, the World Bank expanded the scope of a $220 million programme to address problems in Ghana’s energy sector. In its 2019 assessment it touted the programme’s progress in lowering the losses incurred by Ghana’s main energy utility, the Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG), citing improved billing. On the back of this purported success, the World Bank launched a successor initiative that same year, the Energy Sector Recovery Program (ESRP). This programme boasted disbursement rates of 88 percent, and the World Bank’s assessments of it were glowing. A $55 million smart-meter project won special praise. In June 2024, the Ghanaian parliament greenlit a $250 million scale-up of the project.

But a review performed in 2022 by Ghana’s national audit service, did not back up these positive assessments. The audit revealed that, in attempts to curb daily losses of $2.1 million due in large part to poor billing, ECG spent more than $145 million on smart meters without obtaining value for money. This also contributed to a 39.5% shortfall in the required supply. Amidst multiple procurement law violations, some contractors failed to supply any meters at all, and the frustratingly long wait times Ghanaians experience trying to secure a meter have not improved, with some customers staying on the waiting list for as long as 504 days (despite the official waiting time being 5 days). Meanwhile, ECG’s losses have increased since the World Bank’s latest energy sector intervention began in 2022, from 30.6 that year to nearly 40 percent today, according to John Jinapor, Ghana’s minister of energy and petroleum. An assessment for an energy sector regulator, the PURC, by accounting firm, PwC, shows that the financial shortfall in Ghana’s electricity sector now stands at $8 billion, amidst massive revenue misrepresentation by ECG.

It took a new government and a fresh set of eyes to discover that ECG officials have been importing large amounts of supplies outside their procurement plan, failed to clear them from the ports, and somehow allowed these materials to end up in scrapyards all over the city of Accra. An official investigation revealed that 1347 containers, out of 2491 investigated, containing critical supplies could not be accounted for. The sheer scale of these losses controvert much of the World Bank’s reporting on the success of the ESMP.

The Compromise game often involves doubling down in the face of adversity

Between 2006 and 2014, the World Bank also helped fund a $60 million digitalization project in Ghana, which was meant to apply the transformational power of ICTs to enhance national competitiveness. The cost was split 60-40 between the World Bank and European donors. Its successor programme –launched in 2015 and called e-Transform – was designed to scale up what had worked. E-Transform’s disbursement rates hit 74 percent in 2020. According to a 2015 World Bank report, a platform to automate public sector payments and accounting constituted “one of the major accomplishments of the project.” The global lender hailed this platform’s success in “improving the efficiency of government functions,” credited it specifically for facilitating improvements to Ghana’s “budget formulation and execution” and financial reporting, and boasted that it had allowed the Ghanaian government a “more transparent use of funds.”

The European countries that co-funded the programme, however, disputed the World Bank’s findings. Their reading of the joint audits in 2014 showed that at best, only 60% of the platform’s features could be said to have been implemented. They pointed to Ghana’s persistent challenges with public financial management – such as arrears, overspending, extra-budget allocations, and slippages – that a well-functioning automated payments platform should be able to address. Unable to make progress with the World Bank, in October 2013, the EU and bilateral donors decided to withdraw from active monitoring and evaluation and stay on only as observers. In a 2022 review, Ghana’s auditor general highlighted similar challenges, revealing that more than 86 percent of government payments that were supposed to be handled by the automated system bypassed it due to poor controls. The inability to fix project challenges over a decade corroborates the concerns we have raised about how the World Bank’s supervisory process can prolong the delivery span of projects without necessarily getting governments to substantially comply.

Independent analysts’ reviews of all the other major components of e-Transform – such as digital health and so-called e-Justice initiatives, which were supposed to transform health systems and justice delivery – reveal the same gaps between what is described in World Bank reports, obviously as an outcome of the standard oversight process, and how beneficiaries actually experience the end-product. The outcome of a so-called e-Immigration project was particularly telling.

This project was meant to support automated immigration clearance at Ghana’s main ports using biometric e-gates, digital visa processing, and the phasing out of paper-based procedures across all borders. The e-gate infrastructure and software alone were budgeted at nearly $20 million. Central to the vision was a Secure Border Management System (SBMS) to facilitate screening of visitors, which was meant to replace a U.S.-donated platform.

But six years after the system was scheduled to launch, the U.S.-donated system remains in place at Ghana’s sole international airport. Even though the outcomes of the e-Immigration programme are documented as successful in World Bank reports issued in 2020, neither the new border-management system nor any of the multimillion-dollar e-gates procured with World Bank funds were ever installed in the international terminal as promised. Late last year, the government signed a fresh contract with a Ghanaian contractor at a total cost of nearly $300 million over a ten-year period to supply the same e-gates and secure border platforms described as successfully delivered in the aforementioned World Bank reports. Somehow, the World Bank funded e-gates simply didn’t work for the country, notwithstanding the funds expended.

The reason for this situation – where, from the World Bank’s point of view, a project has been completed and yet the impact cannot be felt by beneficiaries on the ground – is the same as in the previous episodes. There is often significant divergence in the government’s approach to things and the World Bank’s implementation culture, yet there is a shared interest in getting disbursements through. A cat and mouse game thus results in which ultimately some administrative settlements allow projects to proceed to a close – i.e. the “compromise game” – but often with significant delays and considerable tolerated waste.

According to the World Bank’s reports on the e-Immigration system, the multi-million-dollar e-visa system did commence operations in February 2019. The only challenge is that, according to our direct verification work, it could not be deployed to any of Ghana’s more than 70 diplomatic missions. Individual missions have engaged private service providers to build and manage separate visa-processing systems at their own cost. In 2024 the country’s Foreign Ministry signed an opaque deal with an obscure entity to take over visa processing. The deal gives the contractor pre-emptive rights to provide technology in the event of any future attempt to introduce a e-visa platform, clear evidence that the World Bank-sponsored e-visa programme failed.

Yet in 2020, the global lender agreed to extend e-Transform for a further four years, even more than doubling its commitment from $97 million to $212 million. This, despite the fact that some e-Transform initiatives, such as an effort digitize Ghana’s tax collections, have been outright abandoned. In 2024, the revenue authorities replaced the tax application with a new solution that a former chairman of the tax authority described as “immoral, unpatriotic, and evil.”

Turbocharging disbursements does not sustainably solve the constriction problem

Ghana’s experience demonstrates that boosting disbursement alone does not guarantee better development outcomes. Thus, whilst the first stage of the constriction problem can be addressed by renewed political interest in World Bank facilities as happened in Ghana in the 2010s and more recently in Ethiopia, sustaining an improvement in ways that benefit communities require deeper shifts in the normative handshake between the World Bank and the society, not just the government, more broadly.

Because, ultimately, the core problem with World Bank programmes comes down to inadequate oversight coupled with a mismatch between the sophistication of some of those project objectives and the host government’s willingness to step up its capacity to meet those objectives. As far back as 1964, the World Bank itself had come to that same conclusion.

Without sufficient interest from citizens, however, the political incentives for such steep climbs will always be low. A World Bank oversight system limited to a few technocrats on its and the government’s sides would never deliver such political incentives.

At best, it would only perpetuate the current cat-and-mouse compromise game in which projects are drawn out, disbursements staggered through in bursts and trickles, and significant resources that could have had a transformative effect in the lives of people fail to deliver optimally.

As analysts in other countries such as Kenya have shown, the challenge is not limited to the peculiar political economy of Ghana.

At any rate, the evidence from Ghana clearly suggests that even boosting effective disbursement rates will not be enough to address the absorption problem that prevents World Bank loans from being spent effectively. Attempts to force-feed recipient countries more funds will likely lead to projects officially marked as finished but with underwhelming impacts. It is also clear that the World Bank’s process for rating countries’ government capacity, the CPIA, has to be rethought and redesigned to reveal the areas of true weakness in a country’s capacity to effectively deploy development finance.

Moreover, even though the World Bank purports to base its IDA fund allocation decisions on how well countries perform on the CPIA, the actual computations and trends for specific countries in terms of CPIA-linked disbursements have never been transparent. Citizens can’t track what they don’t know.

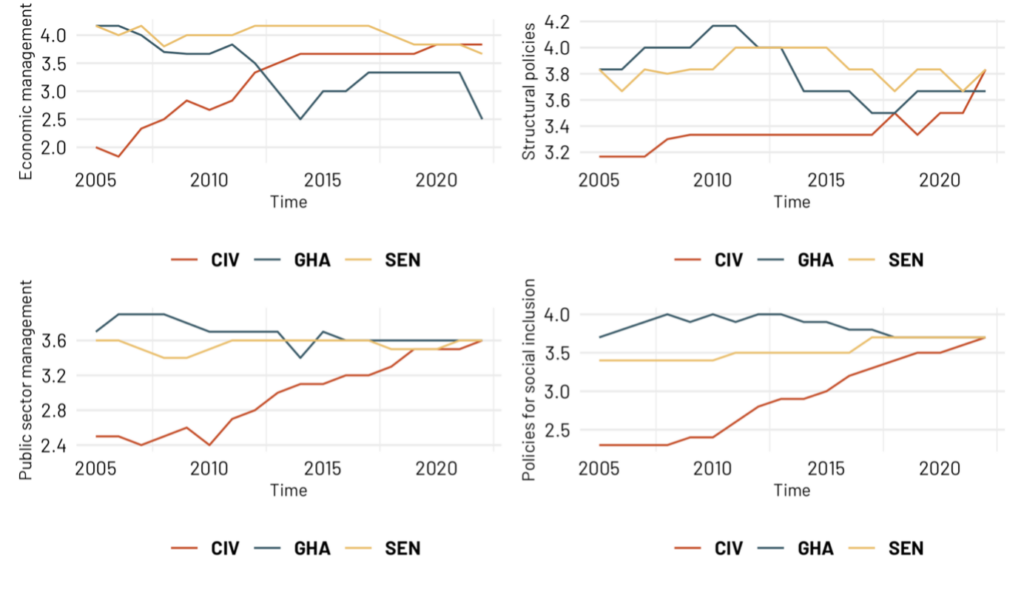

A comparison between Ghana and two other West African countries of similar size and economic composition—Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal—reveals that Ghana’s economic management has stagnated in areas that are highly correlated with the effective disbursement of development finance. The country’s overall rating on the CPIA, which is generally satisfactory, does not x-ray the critical gaps well enough. A country may score highly on certain aspects of democratic governance, such as the quality of its elections, and still fall short in the areas of management most important to properly using development finance.

The finding discloses something profound: countries that perform well on voice and accountability indices due to their vibrant democratic cultures, such as Ghana and Kenya, may nevertheless underperform in policy checks and balances because political accountability is not the same as policy accountability. Elsewhere I have used the term, katanomics, to expound on this point.

Yet, technocratic donor projects, such as those funded by the World Bank, are more policy-centric than politics-centric. Without a national policy audience of a certain size, policy accountability becomes very difficult. Worse still, political vibrancy can actually cloud national judgement in such a situation by distracting from critical policy matters. A phenomenon that may be likened to a “political voice disorder”, or dysphonia.

The linked metaphors of katanomics and dysphonia explains the paradox of some countries in Africa that appear to increase in democratic performance only to seemingly backslide on economic governance. The World Bank may wish to submit to this reality and deliberately invest to expand the national audiences for its projects. Doing so would serve to deepen and enrich policy accountability in ways relevant to genuine, non-compromise based, performance. In the last section of this paper, we expound on how.

Conclusion: contrasting the cyclops and argos models of governance

As we have seen, addressing the World Bank’s malabsorption and constriction problems will require a far more surgical intervention to unclog the tubes than merely boosting capital.

The World Bank pays extensive lip service to the role of civil society actors in helping implement and oversee its projects. But it has clearly failed to listen to domestic watchdogs that understand the local political economy and have no programme-related conflicts of interest. Yet, such actors are critical in disrupting the cat-and-mouse dance between governments and the World Bank as they can crowd in the interests of ultimate beneficiaries thus ensuring that administrative contrivances do not override a focus on substantial social impact.

To make headway in tackling the governance morass preventing the maximisation of World Bank resource effects, a number of steps are required.

First, the World Bank’s broad performance index, the CPIA, has to be redesigned to show the areas of true weakness in a country’s capacity to effectively deploy development finance. Ghana’s economic management, for example, has stagnated in areas that are particularly strongly correlated with the effective disbursement of development finance. The country’s overall rating on the CPIA, which is generally satisfactory, does not x-ray the critical gaps well enough. A set of indicators linked directly to the government’s capacity to deliver on key priorities within the country partnership framework would be helpful.

Second, the performance-based disbursement model of IDA funds needs to be unpacked, made transparent, and positioned as the fulcrum of dialogue with domestic civil society. After which the framework must be extended to all World Bank sovereign funding.

Third, the structural conflict of interest in project design and supervision must end. As it stands, the same people who are deeply involved in setting up programmes are the ones who monitor its ongoing effectiveness. This model is failing. To amplify independent voices, the Accountability Teams in the World Bank must be empowered to establish independent stakeholder panels to solicit unbiased feedback on project and programme efficacy throughout the design and implementation cycle. The bank must also transparently budget for this much higher degree of civil society involvement in each programme’s execution cycle.

Forth, the seriousness of the situation further calls for the World Bank’s review process to become truly iterative. Additional financing, extensions of a project’s scope, and the launch of successor programmes must be driven by insights into past performance from unbiased local watchdogs. The bank could make far better use of new technologies to continuously monitor and review projects: digital tools such as interactive QR coding and Electronic Visibility Platforms, for instance, could collect impressions from ordinary citizens impacted directly by execution delays and malfunctions throughout a project’s execution.

Private-sector executors of programmes, World Bank staff, civil society watchdogs, government officials, and citizens must also work more closely together in this endeavour. This is more challenging than it sounds: other development finance institutions such as the Global Fund have experimented with creating broader oversight forums. But their efforts have often fallen short due to a lack of key performance indicators and delays in hiring and training full-time staff. In many cases, however, there is no need for a new bureaucracy to improve oversight: civil society organisations in Ghana and elsewhere, despite operating on shoestring budgets, are already performing serious scrutiny. The World Bank just need to become more willing to consider their insights.

All of these improvements would constitute changes to the global lender’s culture. They would have to be instituted by the very same World Bank that has, to date, resisted them. But if the Bank is truly open to reform, then it could launch a once in a generation citizen mobilisation drive for development. Something that should over time outstrip any capital raise it can muster in sheer transformational impact.

The World Bank’s projects in Ghana show that the bank does, in fact, have staff dedicated to restraining waste and holistically addressing constriction: in 2020, Ghana set up its own development bank with financial backing from the Ghanaian government, European development finance institutions, and the World Bank. During the period when the project was being incubated at Ghana’s Ministry of Finance, World Bank staff were ruthless in demanding compliance with procurement standards. To get around this oversight, Ghanaian officials simply postponed procurement until the new development bank attained some autonomy, after which alarming procurement abuses ensued.

So long as the World Bank relies almost entirely on centralised deterrence, its funding programmes will court such mishaps and waste. This may be termed the “cyclops” problem, a hundred-handed beast with one roving eye, prone to strain. The solution is to embrace “argos,” the hundred-eyed guardian in the ancient myths. That new Ghanaian development bank I mentioned earlier did have internal auditors and compliance officers who worked hard to uncover the procurement abuses. But it was the intervention of civil society activists that got social media excited about the topic, compelling the World Bank to announce an investigation.

This shows how local assessors and watchdogs, embedded in their country’s political economy, and thus immune to the charge of neocolonialism, are today the underutilised companions of the world’s development odyssey. But that can change; new policy can empower and unleash them.

At this moment in history, when we are observing the literal dismemberment of hallowed global aid agencies and millions are risking death, the World Bank has no choice but to clean up its act and step more confidently into the vacuum. As we hope we have demonstrated in this essay, it could literally double its effective financing capacity by loosening constriction and minimising waste, thereby plugging the larger proportion of the capital hole in global development finance today.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.