It is exactly two months ago that the BBC dropped a bombshell documentary about dangerous opioids flooding some West African countries like Ghana.

What was bizarre about the video was the involvement of otherwise respectable companies in what is essentially a trade in poisons. I was led to conclude that these dangerous drugs were not being smuggled into Ghana. They were being imported and distributed in plain sight.

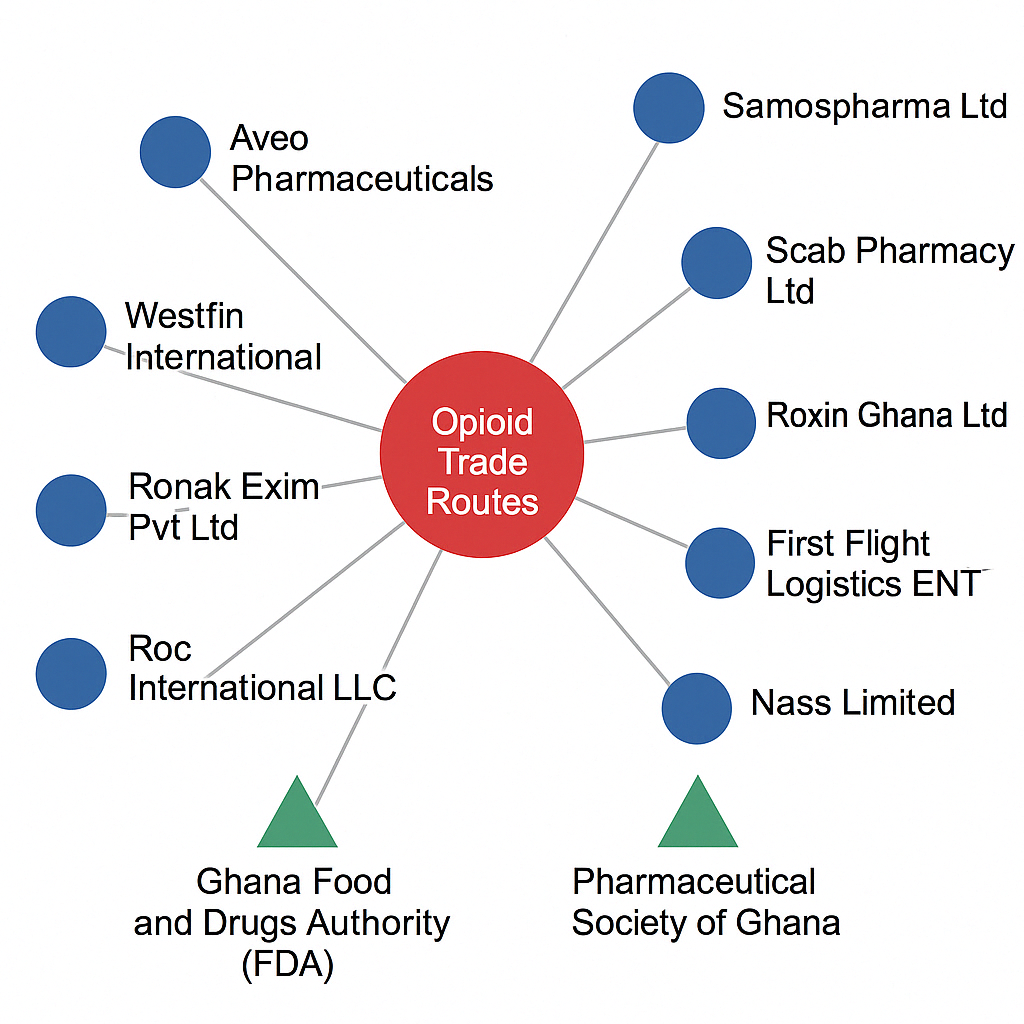

What followed after the documentary’s release was nothing short of bizarre. The main Ghanaian pharmaceutical regulator, the FDA, appeared to confirm that the kingpin exporter of these opioids, Aveo, and its affiliates, especially Westfin, were registered business partners of Samospharma, the company cited in the documentary for importing and retailing some of the drugs through outlets bearing the brand of its award-winning e-pharma platform, DrugNet.

Samospharma exploded with fury, threatened to sue the BBC, and described the FDA’s registration records and public statement as bogus. It demanded a public retraction and an apology.

Detour (you can skip this section): Katanomics & Political Dysphonia

Those of us in the public advocacy space in Ghana have become used to a phenomenon whereby every issue, no matter how sensitive or important, is considered, “debatable”. After some dramatic finger-pointing, shouting matches, kangaroo-dancing, and all-round cacophony in the media, the “debate” dies down and no one is none the wiser about what exactly was learnt or done.

I have found that this problem is particularly acute in our policy contexts due to the gulf between political accountability and policy accountability (a phenomenon I have termed, “katanomics“). A vibrant democratic culture may guarantee a higher level of generic political accountability, especially through the ballot box, but it does not necessarily lead to policy accountability.

Policy accountability requires the “national audience for policy” to constitute a critical mass capable of shifting the political pendulum. In Ghana, this is not the case. Thus, democracy-induced vibrant media discussions actually serve to distract, obscure, cloud, and confuse. It leads to a “voice disorder”, political dysphonia. The citizenry have a lot of voice, but it does not lead to meaningful policy accountability.

Political dysphonia explains the paradox whereby highly democratic countries in Africa that also suffer a degree of katanomics tend to have weaker policy accountability, by which I mean government officials tend to get away with policy underperformance.

Performativity vs Performance

Because the critical national audience for policy in Ghana is rather small and weak, when an issue such as opioids pouring into the country through formal channels come up, relevant public officials only need to set up some “performances” to “close” the issue. It is not their performance in addressing the policy defect, gap, or problem that matters; it is their “performative” ability to declare the issue resolved through appropriate spectacle.

In the specific case of the opioids mess, the Health Minister did not miss the opportunity to display. A bonfire was set up and some consignment of opioids apparently being trans-shipped to Niger were seized and conflagrated. This week, the security services upped the burning ante. Cameras, light, action!

Weeks later, no information has been forthcoming as to how exactly products unregistered for sale in Ghana, and some outrightly banned around the world, were allowed to come through legal channels and sold in the open. No one has been held accountable along the chain of importation, clearance, surveillance, distribution, or sale. In fact, everything has been done to avoid public explanations of the exact causal links and process sequences involved in the breaches so obvious and manifest on the record.

What about Civil Society?

Granted that the Civil Society movement in Ghana, sections of which constitute the core national audiences for various important policies in the country, is small and weak. Still, what have we been doing within our limited resources?

Quite a bit actually. We have continued to gather intel and data across multiple government agencies, international media partners, and trade networks. In the last two months, we have built various analytical algorithms, drawing on the growing strengths of AI platforms to narrow down on the most essential aspects of the problem.

The findings are overwhelming

Let me first off say that I was shocked about what we have uncovered so far. The problem is deep, broad, and totally perplexing.

What we have said already is that one company seemed to have become a node in the trafficking network. The company however insists that its brand has been criminally impersonated. The regulatory and security services appear totally incapable of unravelling the mystery.

So, we employed our algorithms to construct an analytical web of ego networks to help us dig further into the mystery.

In this brief essay, we will outline some of our findings to date and use the opportunity to suggest that the ongoing controversies about narcotics trafficking in Ghana exhibit similar characteristics. We do not have confidence in the ability of the regulatory and security authorities to be transparent and candid about the issues.

The recent circus around purported intelligence tips to the effect that a major global medical ambulance operator is smuggling cocaine into Ghana reeks of the same “performative”, katanomic, and distractive methods used to undermine genuine accountability. More citizens would have to get involved in collaborative investigations for the situation to see any improvement.

Now, for the results

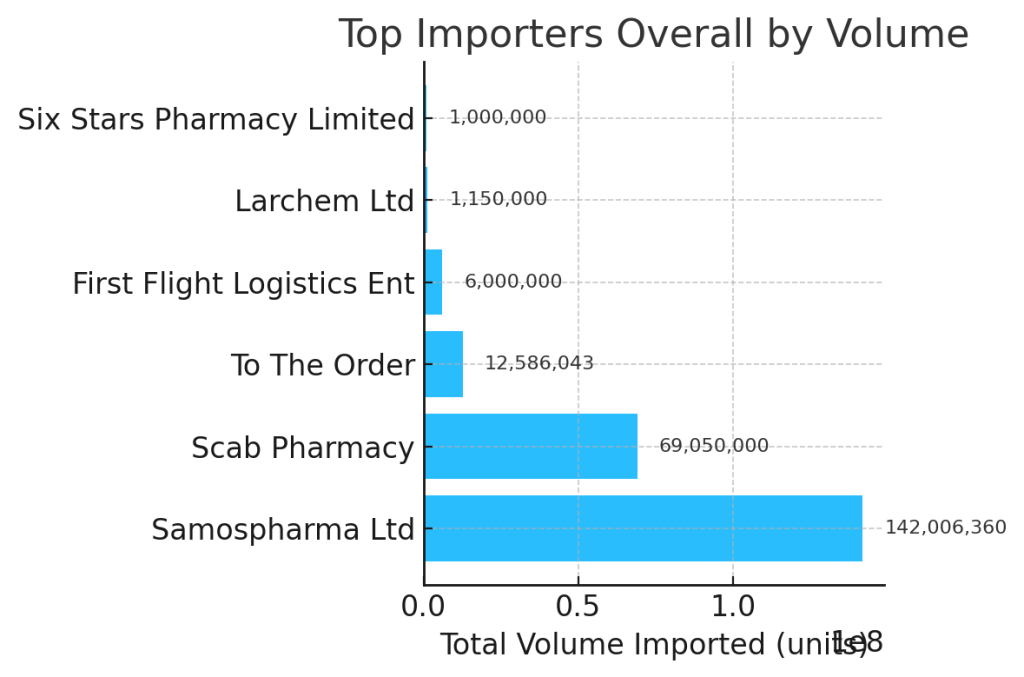

- The first key insight from our analysis is that beyond the companies mentioned in the documentary, several other individuals and corporate entities surface when market intel is analysed. The chart below represents one slice of data for a limited horizon. Note the suggestion of over 200 million units of opioids entering the country over what is a limited time horizon!

2. One actor that intrigued us is the entity associated with one Dr. Bandoh who has been reported as a major supporter of the University for Health & Allied Sciences’ School of Pharmacy. Our intrigue stems from the sophisticated e-commerce capabilities of the entity, and the rather interesting sale of prescription-only 100mg Tramadol products online.

Despite the FDA’s strong insistence that it has not licensed tapentadol, one of the two main ingredients in the incredibly dangerous and globally banned tafrodol product, for use in Ghana, there were e-commerce portals stocking the product early this year. Recent online searches, however, produce “out-of-stock” responses.

3. Linked to the e-commerce point above, we noticed also that some companies purportedly in the software industry are somehow mentioned as importers of opioids from the company at the center of the BBC documentary, Aveo, in the trade-intel databases.

4. Aveo’s introduction of Westfin to create an arms-length distribution network saw a sudden boom in shipments in early 2023.

5. The spike in the above graph does not necessarily imply “peaking”, though. The seasonality in shipments rather corresponds to the market’s ability absorb an ever expanding quantity of the illegal drugs since the pandemic. It would appear that levelling-off periods shrank. Below is a chart for Timaking, one of the new opioids supplanting tramadol on the market.

6. After Westfin’s entry, we also see an interesting spike in the activity of individuals in the importation business. Since Ghanaian law grants importation permits to only companies, the involvement of individuals in the trade is totally shocking and baffling.

7. For many of the consignments flagged in recent investigations that consignees have disowned and alleged impersonation, we found that source countries were set to South Africa and Egypt even though the products originated in India. Furthermore, our investigations established that the subsidiary details provided for the mother companies in India in these African countries (Egypt and South Africa) do not check out.

8. In effect, the current system is so porous to the extent where even consignment origination cannot be accurately established.

9. We corroborated the claims made in the BBC documentary that Ghana has become such a soft touch for traffickers that Nigerian importers of the banned opioids are openly using Ghanaian ports to bring in the products and then transport across the border. We name two such companies below.

10. We further confirmed that the banned and other dangerous opioids are cleared from the port by fully registered and authorised clearing agents who openly sign for them and pay all the necessary fees and charges. Everything is done in plain sight. Any impersonation therefore must either be officially sanctioned or done with the connivance of national security actors overriding the standard checks by FDA and customs officials.

11. For example, in the dramatic standoff between Samospharma and the FDA, the issue of the right manufacturer of prolatan eye-drops featured strongly. Even though Samospharma insists on having registered Sudarshan as the manufacturer and exporter, the FDA’s records suggest the involvement of Aveo, the company in the eye of the BBC investigative storm. The official clearance trail at the entry port shows that Duncan International Ghana Limited cleared consignments originating from Aveo purportedly on Samospharma’s behalf (sample bills of export: 41023472254 & 41023472239). This is a long-established port operator with a footprint dating back to the 1990s. In other instances, Hans Shipping Services Limited is the operator involved (sample bill of export: 40823359065). Hans is likewise a very well established service provider in the industry whose customers include even some corporate household names. Indeed, in the ongoing “missing containers” controversy, investigations have confirmed that when ECG awarded clearing services to Mint Logistics, which lacked the capacity to execute the job, it was Hans Shipping Services that stepped in to save the day.

12. Our ego network analysis shows a set of patterns around e-commerce/online-retail portals, established clearing service providers, legitimate pharmaceutical companies, and international/regional logistics companies all seemingly working together in above-board transactions that somehow appear to result in hundreds of millions of dangerous opioid pills entering Ghana. The inability of the security and regulatory services to impugn these open and transparent transactions and actors lend credence to the allegations that have been made that powerful players are using legal fronts to mask some really nation-wrecking activities.

If purely open and transparent transactions in a highly regulated industry like pharmaceuticals can nonetheless mask such sinister dealings, then what hope can Ghana have that truly clandestine criminal activity like cocaine trafficking can be unraveled to expose the players behind? Clearly, the “system” is much too compromised for any such hopes to be entertained.

For now, Ghanaians may have to rest content with wild and entertaining claims of international medical ambulances sneaking cocaine into the country in their cockpits.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.